Horology is a huge part of my life. It’s my biggest passion. So, naturally, it pains me to say that not much in the world of watches blows me away anymore. The truth is, I have been very lucky. Many of the people that I am fortunate to call my friends happen to be some of the world’s most recognised collectors of horology. Living in Los Angeles also helps. With watch boutiques galore and a steadily-growing network of collectors, I find myself attending a watch-related event seemingly every week. Not only do I get to see, play with and wear some amazing watches, I get to do it with a belly full of hors d’oeuvres, washed down by endlessly-flowing, top-shelf liquor conveniently delivered via silver platter by the next Denzel Washington, or better yet, the next Scarlett Johansson. It’s a tough life, I know.

All kidding aside, that type of exposure has desensitised me a bit. I used to light up when given the opportunity to witness the mechanical complexity of a perpetual calendar, or to hold a watch showcasing the beautifully hypnotising, and gravity defying acrobatics of an exposed tourbillion. Complications used to be special, but now all they seem to be are the watch industry’s defense mechanism. Pun completely intended.

Intricate parts that used to take weeks to make can now be stamped out by automated machines in minutes. The parts are then handed off to watchmakers, or “assembly workers” as I like to call them, who promptly and efficiently pump out watches in numbers that are truly impressive. A market flooded with watches that have the same old complication fitted to a familiar regurgitated design shortly follows. There is an upside here, however. More precise and higher quality components result in great wristwatches, and there are without question a lot of great watches on the market.

But great is not enough for those obsessed with horology. Great is for logical and sensible people. The kind of people that purchase a Rolex Submariner to celebrate ten absence-free years at the firm… for themselves. Our kind is far from logical. We yearn for emotional attachment. We’re the type of people that buy and sell the same watch several times over just to see if we miss it when it’s gone. If it’s just great, I can promise you it won’t be missed. To make watches more than great requires creativity, and an obsession for what horology is in its purest form – mechanical art.

To escape the monotone cacophony of commercialised horology, I decided to immerse myself in the emerging world of independent watchmaking where the watchmaker once again reigned king. I discovered the once thought to be extinct atelier style of watchmaking quietly thriving in various tiny workshops scattered around the world. Japan, Russia, Sweden, and countless others were all home to independents. All with their own style, all with their own obsession for horology. Watchmaking was not dead.

Along this journey, I found myself impatiently staring at the startup screen of my trusty MacBook early in the morning. I barely slept the night before, but I was strangely wide awake and energised. My Skype account was charged up with ten-dollars’ worth of credits that I loaded the previous night just in case. I entered the country code and number. Immediately after I clicked the blue headset an unfamiliar dial tone rang loudly in my ears. I couldn’t remember the last time I was nervous interviewing someone, but this time I was. I have never spoken to someone commonly attributed as being the “world’s best”. At the end of the second dial tone my mind was all over the place. I kept thinking “I hope I don’t sound like a bumbling idiot, I hope that I can at least construct a sentence”. All the sudden, I hear it, a gentlemanly “hello Michael”. Stupidly I respond with “Roger?” as if I called the wrong person who coincidently happened to expect a call from someone called Michael. As if that wasn’t enough, after an awkward pause, I blurted out “good morning!”, even though he was eight hours ahead, and for him it was 4 in the afternoon. Luckily, I never reached a third moment of dull-witted speech on that call. My nervousness dissipated as I shifted my focus on learning about a man and his work. We spoke for just under an hour.

Roger W. Smith is not the typical face of modern horology. He is not a geared up and ready-to-talk-my-ear off Gucci suited CEO of a major brand with the ulterior motive of “sell, sell, sell!”. He has no need to go on about how revolutionary his new cases made of forged carbon ceramic titanium layered with carbide are capable of withstanding repeated assaults by what is the bane of a watch wearers existence – a door knob.

That’s all nonsense to the only man on this planet with a skillset impressive enough to earn the late George Daniels’ blessing to build a series of watches bearing the Daniels name. Prior to that achievement, he was also Daniels’ one and only proper apprentice. With those type of credentials, you would think that staying humble would be as big of a challenge for him as crafting a watch from scratch, but he has more important things to do than to flaunt his non-existent ego.

Instead, Smith is on a mission to reestablish Great Britain as the cradle of high horology. He is fueled by the legacies of British watchmakers before him, who prior to the Swiss were the world’s elite timekeepers. Hear that ticking resonating from the Swiss Made Patek Philippe on your wrist? That’s coming from something called the “Swiss lever escapement”, an improvement on the lever escapement, invented by Thomas Tompion, a Brit. Or perhaps you have chosen to wear an Omega with “Co-Axial” stamped on the dial instead? In that case, your Swiss Watch, once again, has a British heartbeat courtesy of Roger’s mentor, George Daniels. But bringing an entire country back into the forefront of horological glory needs something more than heritage and the development of specific enhancements to watchmaking, it needs Smith and the ten hand-built watches that leave his workshop every year. That’s right, just ten, so if you want one, prepare to wait. A lot. It’s worth it, trust me.

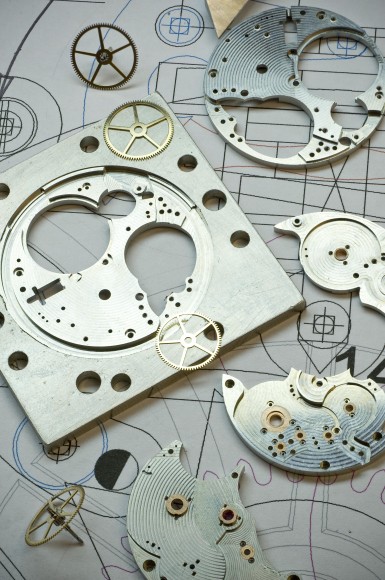

Every new Roger W. Smith timepiece begins in the form of a sketch, done of course, by hand. With the dimensions jotted, and calculations finalised, all without the use of computers mind you, the time to make a watch has approached. It all starts with a single rod of gold or platinum that is hand bent, and torched repeatedly in the hope of achieving a perfect circle that will eventually become just one out of the three necessary components of a watch case. Room for error doesn’t exist within these workshops walls. There are few machines here, and apart from a modern CNC, they’re all somewhat archaic. None of them possess the ability to save Smith and his team from anything less than masterful operation. He relies solely on the brilliant communication that is the delicate yet powerful dance between his mind and his hands to control them, millimeter by millimeter.

Of the thirty-four skills of watchmaking that are known as the Daniels method, Roger and his team utilise all but two – balance spring making and engraving. That means that a Roger W. Smith timepiece is quite possibly the clearest definition of what it means to be “in-house”. Correction, British in-house. This makes a difference.

So, if he’s so talented, why can’t he form a tiny little spring and engrave a bridge or two? The answer is simple. The most powerful watch brand, Rolex, only recently mastered the art of making the balance spring after Millions in research and development. Before that, like nearly all manufacturers and watchmakers, Swiss and beyond, Rolex bought the springs from suppliers. And engraving? He leaves that up to someone whose only craft is engraving. Besides, as he said himself on the call, he’s more “practically orientated” anyway, so cut the man a little slack, will you?

Was all this mastery the reason I was nervous to interview him? No, I was nervous because before our call I experienced a Roger W. Smith timepiece in person, albeit with “Daniels” name on the dial. The Daniels Anniversary Watch, numbered 35/35 by the request of the owner, rested in front of me for quite the while before I mustered up the courage to pick it up, even though I was closest to it in proximity. I was the last person to touch it for a reason.

I hesitated not because of its value, nor due to its rarity. This was my “I have been to the mountaintop” moment. How would it make me feel compared to everything that I have ever owned and experienced? Would it completely ruin all other watches for me? Or worse yet, would it disappoint me and send me back into the depressive spiral that I was attempting to claw myself out from?

The room was not well lit, and just to the right of me was a bottle of 12-year old Scotch. I considered taking down a few drams to ease myself but ahead of me was a drive home, so I refrained. As the few people in the room whirled around the seven other marvels of horology sharing the same table, I reached out with my right hand, grasped the watch securely, and proceeded to move it closer to my line of sight. Undenounced to me, somehow that same motion resulted in me being no longer seated.

Standing still, head tilted and with both hands on the watch, it was clear that what I was holding was far and beyond anything I had ever experienced, watch related or not. Slowly, I made my way over to better lighting, away from the horological banter, and began to do what every horology junky does. Every angle, every detail, every shape, was examined. The cynic in me was looking for it, but not a sign. Not a single flaw.

It all began with the dial. The simple, yet highly complex symphony of dials and sub-dials surrounded by gold chapter rings was symmetrical perfection. Inside each sub-dial, a different pattern, done completely by hand on an engine turning machine. The hands, all with their own character and shape. The slightest change in light on the dial and there I was, holding a brand-new watch. Amazing.

The case, seamless. Not a clue indicating what used to be three separate rods of raw gold. From afar, it is understated, just like the dial, yet at the same time curvaceous and dominant. The gentle bulge mid case made it strong and powerful visually and by feel. The final test, the movement. A gentle flip, and there it was, the sublime sight of perfectly executed British innovation proudly engraved with “Co-Axial Escapement”.

Aside from the Manx Triskellion quietly residing by the balance wheel, there was no indication of the watches country of origin. Not on the dial, nor on the movement. There were no insecurities held, and nothing to prove about the point of final assembly. The watch hides nothing. As my friend and lucky owner of the watch said, “it’s reserved, it’s powerful, it’s British”. And so is Roger.

This may sound strange, but I felt like I knew Roger before I even spoke with him. Not because I have watched the dozens of YouTube videos of him going through each step to make a bezel, and not because of the countless articles and blog posts about him and his work. I knew him because a piece of Roger W. Smith was right in front of me, in the form of a perfectly imperfect watch.

What happened to me that night was exactly what I had hoped for. I was in the presence of a watch that finally had soul. The partial effort that I was used to with other watches was nowhere to be found. There were no crutches. No scapegoats. I could not find a damn thing to criticise, and that made me nervous, but in a very good way.

In speaking with Roger, I experienced more of same of what I experienced with watch number 35. My guard was up, but there was no expectation nor preparation in having to deal with an upcoming sales pitch. I suppose my nervousness was just excitement in disguise, mixed in with a little bit of “don’t meet your heroes” potential for disappointment. He wouldn’t have been the first independent watchmaker to act like a diva with an ego the size of a hot-air balloon, after all. But that’s not Roger. He’s a nice, easy to talk to guy. Every question I posed him with received a great, and sometimes humorous answer that helped me learn more about him as a person and what his philosophy is on watchmaking.

I found Roger to be very much a purest. He constructs watches the way he believes watches should be constructed, by hand. His watches are focused on timekeeping first and foremost, with legible configurations and movements harnessing the unrivaled accuracy of the Co-Axial Escapement. Along that process, his keen eye and dedication to historically accurate design results in watches that are timeless, bold, supremely beautiful, and quintessentially British. Take a good hard look at his latest creation, the Series 4 if you’re not yet convinced.