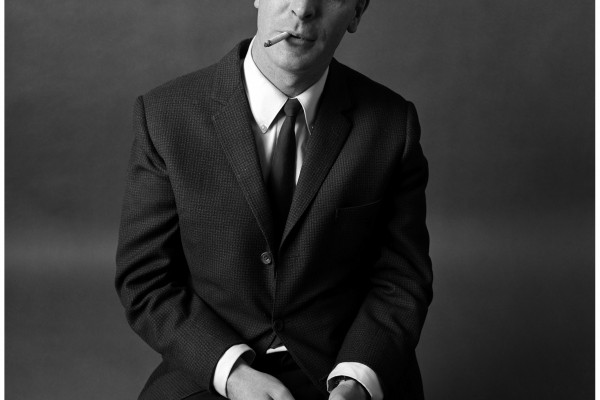

Ben Williams – virtuoso bass player, singer, songwriter, performer and recipient of the Monk prize – is clearly a man who takes his work seriously and isn’t someone who lets a small thing like jetlag get in the way of promoting a record he’s more than justifiably proud of.

During our interview in September, The Review Magazine team sat back on a balmy Monday evening, glasses of rum in their respective hands. Ben Williams, on the other hand, was up bright and early on the other side of the Atlantic, having just flown in from a tour of Japan the night before.

It’s more than characteristic of Williams’ work ethic and dedication to his craft. Unfazed by the ever-present spectre of zoom calls not going quite to plan, our conversation delved deeply into his stunning new album I AM A MAN – his first vocal-led opus, and one which explores issues of racial identity and associated political history while veering between soul, funk, R&B, psychedelia and his signature jazz stylings.

Inspired by the Memphis Sanitation Strikes of 1968, I AM A MAN sits somewhere between a protest record and a wish list for a potential future, made all the more potent when set against the continuing turbulence of past and present. It is, simply put, a fantastic listen with a truly broad appeal, both a meditation on identity and an expression of artistic confidence. Indeed, I AM A MAN remains on The Review team’s playlist, and continuously satisfies with tracks which pack deep grooves, soulful lyricism and impressive musicianship from both Williams and his assembled collaborators.

READ THE INTERVIEW IN THE BEN WILLIAMS EDITION

As with all great artists, Williams’ work is the product of an ongoing creative process. For Ben Williams and every other musician who needs a stage, an audience and that all-important energy exchange in which to realise their craft, the creative process was temporarily threatened by the pandemic and its associated lockdowns.

There’s something fascinating about works – of which I AM A MAN would be included – created during this bizarre blip in contemporary history. As with so many interviews conducted in its aftermath, the subject was never too far from our lips. However, Williams’ personal history, inspirations and achievements (of which there are too many to list) provided fertile ground for a revealing conversation which covered much and suggested even more.

What were you doing out in Japan, and who were you playing with?

We did two shows with (esteemed saxophonist) Kamasi Washington, one out in Tokyo and another at a festival in Yokohama. It was raining hard – it was more like a monsoon – but the fans out there love the music, they love the culture and it was no surprise to see them out in force.

Where is home, post-pandemic?

I moved out of New York about a year and a half ago, and LA is now very much home. I lived in New York for about fourteen years, but moved out here during the pandemic. Obviously it was an interesting time for everybody, but a lot of artists – and a lot of people in general – started to recalibrate and reassess where and how they’re living. I personally know a lot of people who have moved in the past year, looking to live in a more chilled-out area.

How did New York change over the period you were living and working there?

I think probably everybody who ever lived in New York says the same thing; that New York isn’t like it used to be. I watched it change as I lived there… and a good friend of mine always says that New York is for the young and the rich, and I think that’s absolutely right.

The years I lived in the city were great, it was an amazing place to discover yourself as an artist and it’s a place where you can build strong bonds with people. It sounds strange, but there’s almost a shared trauma of living there – we built up a community of artists, but so many of us got out of there when everything started shutting down. Interestingly enough, a lot of those people ended up in LA; we’re reconnecting again, but we all go home a little earlier these days!

In terms of your roots and grounding in DC, what are your earliest memories of music?

I grew up with my brother Todd, and we were raised by our mother Bennie in a household where we were very much into music – it was a big part of how we spent our time. At any family gathering you’d find me at the piano playing songs, with the rest of my family joining in. My mom listened to a lot of music around the house – R&B, James Brown, Isaac Hayes, and Motown classics such as Marvin Gaye, Temptations, Gladys Knight and Diana Ross. She loved lots of gospel music too, while my brother and I played lots of Michael Jackson and Prince, both a big deal at the time.

I was always creatively inclined – I’d draw a lot and was always making something – and so my mom ensured I went to a school with an arts program. That’s when I picked up music. I wanted to play guitar, but the guitar class was full, so I ended up in an orchestral class, surrounded by violins and cellos. The teacher asked me what I wanted to play, and I decided to opt for the biggest instrument in the room – the bass – even though I didn’t really know what it was.

There was a jazz program at my school for a while, and the teacher would introduce us students to Charlie Parker, Miles, and Coltrane, teaching us songs mostly by ear. That’s how I got turned on to jazz, and how I got into learning the history of it.

Playing the bass – it’s a very physical instrument. I got my first big life lesson in the importance of practising when performing at the Congressional Black Caucus Jazz Concert honouring Milt Hinton; I’d spent a while playing the saxophone and had lost the calluses on my fingers needed for playing the bass. I was about twelve years old and ended up with my fingers torn open after the encore. Milt knew exactly what had happened, said some kind words and really just blessed me.

The blessings were abundantly bestowed upon me that evening, for sure. I view it as the beginning of my career at age 12 – I saw myself becoming one of the great bassists of all time, and of course, I’m still working at it. After receiving the torch from the greatest (Milt Hinton), I felt golden and that I was destined for this.

It so happens that my mother had worked for Congressman John Conyers Jr, who was the honorary host of the Annual Jazz Concert of the Congressional Black Caucus. In 1997, my Mother had asked the Congressman if he would invite a youth band to open up that evening’s concert. He agreed, and it was the first time ever that a youth band had performed at his event. A representative from the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz was in attendance, and they offered me private one-on-one bass lessons sponsored by the Institute. That evening literally set the stage for me, and I believe it played a key role in what I’m doing today.

By the way, might I add that my mother’s love for music led her into managing my career following her Congressional retirement, and upon my graduation from Juilliard. She is still actively involved in managing it today. In fact, you will hear her voice speaking behind the music on my latest album, I AM A MAN to the tune of Come Home.

Pat Metheny took you into his Unity band and holds you in high regard – he feels you’re truly above and beyond. Why do you think that is?

Yeah – it means a lot to me coming from him, he was a huge influence on me as an artist and playing with him changed my life. I’d say he is the hardest-working person I’ve ever been around, his seriousness about music and how much he dedicates himself is amazing; he has all kinds of rituals before each gig and watching the process of him putting a project together is mind-blowing. A brave and brilliant man, he was my hero – I’ve been a fan since high school – and I took the opportunity to play with him very seriously.

… and it won you a Grammy, as part of the Unity band.

Yes – not too bad! I wasn’t completely shocked we were nominated – it’s Pat Metheny, and it’s almost just another day, another Grammy for him. I think he’s won twenty across his career, not even counting the nominations. It was all so surreal, but it was an award enough just to do an album with Pat Metheny. The Grammy was just a dream on top of a dream.

When did you start writing I AM A MAN and what were the catalysts for writing a protest album?

In 2017, Congressman Conyers again invited me to be the featured artist at his Annual Jazz Concert of the Congressional Black Caucus – the same event where he had honoured Milt Hinton when I was age 12. I had decided to put together a collection of protest music, exploring the lineage of artists who wrote and performed in that vein. Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan, John Coltrane – I was looking into a whole anthology of protest music, which was the beginning of the project that would become I AM A MAN.

The wheels were then turning on writing music addressing social issues. I was watching a documentary – The 13th, by filmmaker Ava Duvernay – which featured an image from the Sanitation Workers strike of 1968, in which the strikers were holding signs which read ‘I AM A MAN’. Something about it just clicked – thinking about what that phrase meant to them, and then applying it to me and my life as a black male in these times, it became a platform to explore my relationship to the world in which I live. It’s almost where social justice meets therapy and taking social justice to a more introspective space.

My previous albums were primarily instrumental and more in the jazz vein. For this project, however, I had something very specific I wanted to say. I was writing lyrics that were initially intended for other singers. Jose James, one of my collaborators, heard the demos I was working on and said ‘these songs sound great… Who’s that singing?’. When I told him it was me, he encouraged me to do it myself. So I did.

Why is this the first record with you on lead vocals?

It’s just a matter of evolution, for me. I’m always embracing the idea of experimenting and pushing the envelope with sounds, always trying new things. That’s what led me – sonically – to where I arrived with I AM A MAN.

Did you feel, given the subject matter, that the time had come to put your own voice to a project?

Absolutely. I feel like these songs were very therapeutic to create, and singing them, I felt it was a story I needed to tell and a perspective I needed to share. People in this country are aware of these issues – at least, I hope they are – and I wanted to approach it from a personal angle. It was a process of pulling back the curtain; this isn’t just what we see on the TV, it’s also how I feel. I wanted to shine a light on our humanity, our experience in this country, and the process of overcoming injustice. At the same time, we’re all human beings, and we all deal with love, spirituality and life in much the same way.

‘Come Home’ is a really affecting song on the album. How have these songs evolved as a live musical experience?

The album came out in 2020, when shit got a little weird. After the record came out, I wasn’t able to perform these songs. Once everything started opening back up, we were able to explore the experience of performing these songs live in front of a crowd.

For me personally, I had the challenge of learning how to play and sing at the same time – it’s a whole different thing to be at the front of the stage. I’d describe it as being like driving while doing your taxes… all while delivering a podcast. The song ‘If You Hear Me’ was the one on the album I really wanted to try and sing myself first, and from that one song I got the confidence to keep going. Once I started singing at the gigs, I began writing songs with my own voice in mind.

‘Promised Land’ is inspired by Dr. King’s Mountaintop Speech. How did you approach writing the lyrics for that?

That song was actually written as a poem. When you listen to it, you’ll notice it’s written in freeform, with the harmony moving without any particular number of bars. I was tapping into the feeling of a visual in my head: the feeling of listening to and watching this speech and imagining what Dr. King saw as his vision of the future. Bringing that into my perspective, I was trying to imagine what my version of the future might look and sound like – a place that’s free, groovy, and in which we’ve overcome the things we’re fighting for now.

‘If You Hear Me’ has a strong Marvin Gaye vibe – another DC native.

I’ve always had a strong connection with Marvin Gaye, he was an artist I listened to growing up at my mom’s house. Him being from DC – and dying the year I was born – I always felt that there was a spiritual passing on when he left.

The collaboration with Wes Felton – ‘March On’ – has a poetic element. Was it always intended as such?

Yes. The feeling behind that song was to make an anthem of perseverance. We’ve gone through all this emotional content on the record, and I wanted it to end with a feeling of hope and a message that we’re going to keep pushing through, no matter what. Literally, to march on.

When I think of the civil rights movement, we think of marches. Yet marches are usually a military movement, and marching music has that militant feel and uniformity. That’s what I wanted to capture with that groove and beat; there’s a lyrical expression, but beneath there’s the feeling of a thousand people stepping together. I’ve collaborated with Wes Felton a number of times over the years; he’s a real renaissance man and the perfect voice to have on that track.

What’s next?

I have a few things going on. Obviously we’re still touring the album, and keen to get this music in front of people as everything reopens.

However, I’m also working on a film project. It’s an extrapolation of I AM A MAN as a filmed series, and I’m collaborating with a director who I’ve worked alongside a few times before. The songs from the album build a narrative – somewhere between a musical and a dramatic series – and that’s in the early development stages right now, with hopes to start shooting in early 2023. I’m very excited about what that might turn into.

I’ve also got a new band that I started up during the pandemic, Butterfly Black. It’s a collaboration with a singer from Hamilton and the wider Broadway scene – Syndee Winters – and delves into the R&B and soul tradition that we both grew up in. A couple of singles have come out, and early 2023 will see an EP being released.

What’s more important for you: for this album to resonate in terms of the realism of the story, or the ability for it to be received?

I feel it’s both. The beauty of sharing music is that it comes from a sincere place, and a very particular experience. What I’ve tried to do with this album is reflect the experience of being a Black Man in America, but there’s relevance of that experience around the world. I wanted to shine a light on not just my cultural heritage and expression, but on the humanity that exists underneath.

The record is ultimately about identity: I AM A MAN is about a group of men telling the world who they are, because the world they live in is constantly trying to tell them who they are. The right to express ourselves, to tell the world who and what they are – that’s a right that everybody should have, and that’s what unites us all.