I’ve had a very long journey in photography. It’s been a deep, endless passion for me. From the first minute I picked up a camera, I’ve had that passion and, when I was shooting last week, I still had that passion.

When I moved to Los Angeles in 1970, I had only one connection there. He introduced me to the head of Max Factor, who looked at my port- folio and said that he noticed I didn’t have any shots of women (you know, it’s a cosmetics company). I said they’re on the boat coming over, which of course was a fat lie. And he said, ‘I’ll tell you what I’ll do. I’ll give you an hour’s booking with a model. We’ve got some dresses left over in the closet from other shoot- ings. You can take the clothing and do an hour’s shoot.’

READ THE ARTICLE IN THE SPRING EDITION

I went to the modelling agency, and I picked a girl who I thought would be good. I said to her, ‘Would you like to do a long shoot- ing day, and I’ll give you some of the shots for your portfolio?’ She agreed. I went out with my only camera and lens and picked her up at 7.30 in the morning, and I shot until 7.30 at night. All of the money I had, I put into the film. So here I was, going around, shooting her in long grass and on the beach, in adobe houses, et cetera. She brought along a male model friend of hers, and I did pictures of them together.

Three or four days later, I went back to Max Factor for my meeting with all this film. The guy was astonished. He said, ‘Oh my god, how did you manage to do this in an hour?’ And I said, ‘Well, I actually talked the girl into doing a whole day, but she’s charging you for just an hour.’ He looked at the film, said to give him a minute, and went away with three of my rolls. He came back and said, ‘I’ve got good news for you. I’ve just sold three of these images. We’ll buy them from you. Let me know the cost of the film and the process- ing, and I’ll give you a PO.’ (In those days, I didn’t even know that a PO was a purchase order.)

I got into the elevator, ripped open the envelope and, look- ing at the POs, I was thinking, $150 a shot. So that was $450 plus expenses, that’s fantastic! Later, my wife, Elizabeth, was typing out the bill on a school typewriter, when she said, ‘You

know, it’s not $150. It looks like it’s $1,500.’ I thought, That is impossible. (At this point, Elizabeth’s salary was about $1,500 a year.) And we wondered if we should just bill it anyway and hope for the best? And I said, ‘We’re going to get deported, or something, for some sort of crime.’

I had a meeting with the Max Factor guy two days later, and said, ‘I just wanted to clarify the money that was on the purchase order. It was $4,500?’ He said, ‘Well, $4,500 is all we can afford at the moment, but I’ll get you more next time.’ Like I said before, that was my first large, decent-paying job. Although I was a young, inexperienced photographer, I was confident in my abilities and took the risk of agreeing to a project that was completely new to me when the opportunity presented itself. I also worked really hard on it, doing much more than was expected, which certainly helped me to succeed.

As a photographer, you have to stay alert and always be looking for shots. When you’re always looking for shots, shots will come to you.

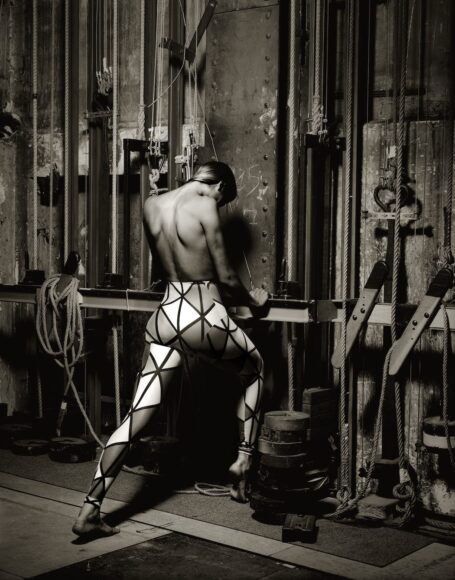

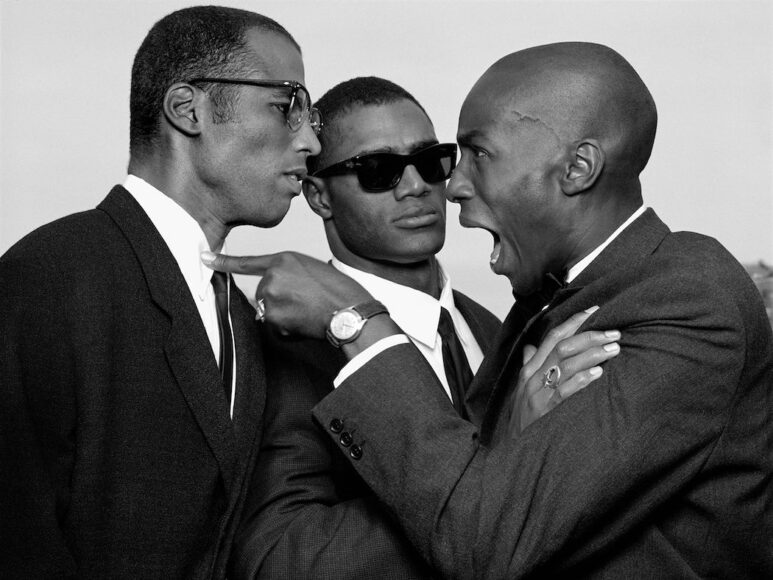

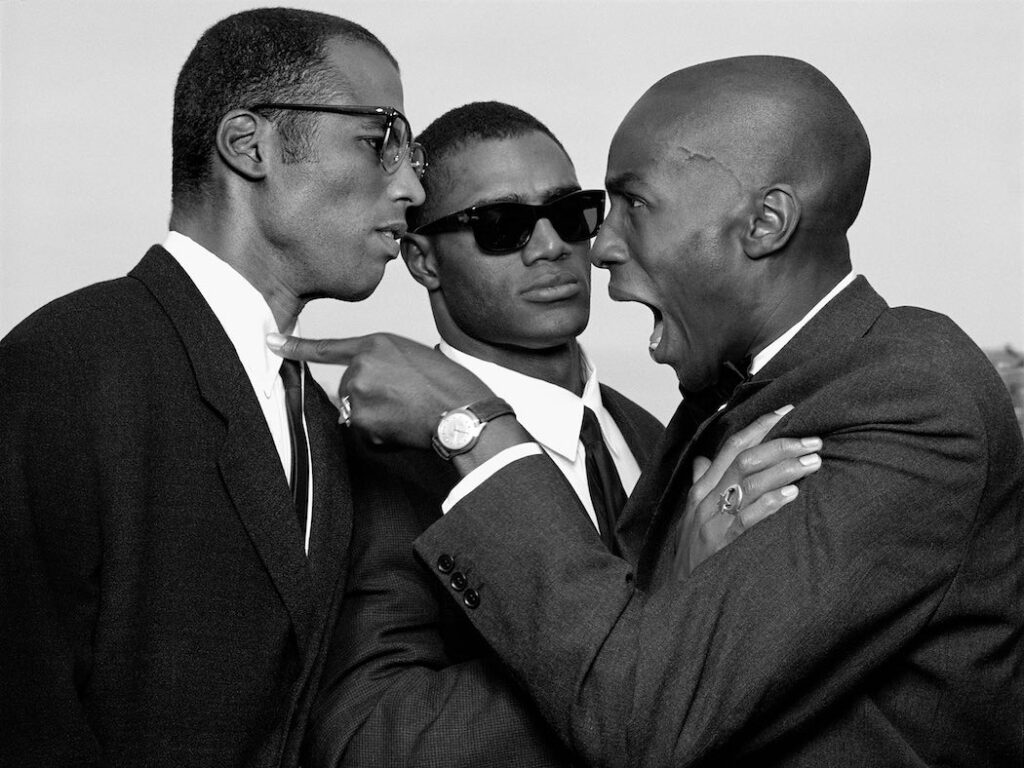

For the 150th issue of The Face magazine, in 1992, I was approached about doing a fashion shoot inspired by the Black nationalist leader and human-rights activist Malcolm X. After a lot of research, I planned a shot with two people, one play- ing Malcolm X and one playing his protégé-turned-denouncer Louis Farrakhan, standing together, basically a portrait. I was in the location vehicle just before I was to do the shot and, on the television, the location driver was playing an old film noir. I looked up, and there were three people on the screen: one person was shouting at another, and the person in the middle was trying to prevent any violence from happening. When I saw that, I immediately got my assistant, put him in a suit and used him as the third person. In the shot, my assistant is on the right- hand side shouting at Malcolm X. So, my assistant became the new Farrakhan (some people suspect Farrakhan had Malcolm X killed), and the guy in the middle became a bodyguard of Malcolm X, as it were. The shot was created by something that I had seen minutes before in an old film. I was able to knit com- positionally something that I’d seen by chance, from a movie, and do an interpretation five minutes later.

In 1973, I was in my studio in Los Ange- les when the phone rang. It was the head of Harper’s Bazaar. At that time, I wasn’t working for any magazine, so I was very excited that Harper’s Bazaar was calling me. The man on the phone asked if I’d photographed anybody famous before. I said, ‘Yeah, one or two.’ (Of course, I hadn’t photographed anyone famous.) He said, ‘We’d like you to photograph some- body a week from now, and we’ll call you tomorrow and let you know who it is.’ The next day, they told me it was the film direc- tor Alfred Hitchcock.

I was just out of film school, so I was both overwhelmed and very excited about photographing Alfred Hitchcock. As it turns out, Hitchcock was a gourmet cook. He was going to give the mag- azine a goose recipe for the Christmas issue, and they needed me to photograph him to accompany the text.

They said they wanted Hitchcock to hold the plate with a cooked goose on it, but I was a little bit nervous that he might look like a maître d’. I called them back the next day and said, ‘I don’t mind doing the cooked goose, but I think it might be better if he’s holding the plucked goose by the neck, like he’d strangled it. I’ll put some Christmas decorations around the goose’s neck. It seems to me a little bit more Hitchcock.’ The creative director said he’d get back to me. He called back half an hour later and said the editor-in-chief loved the idea. They thought it was more fun, and, of course, it is more fun. The Hitchcock portrait is one of the most important shots that I’ve done, because it really changed my career at that point.

With both Max Factor and Hitchcock, even though I didn’t have the specific experience they were looking for, I took a risk and worked very hard to give the client something far beyond what they’d expected. It just goes to show that if you can ever get your foot in the door, the creative door, and then force it open, you can produce some very good stuff. Never let an opportunity pass you by, even if you think you’re underqualified. Just go for it.

Books have played a big role in informing my work, and I’ve always surrounded myself with a lot of them. But, at the beginning of my career, I couldn’t afford a lot, so I would pick up photography-auction catalogues from Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips. I loved that they were so varied. You would have nineteenth-century photography, photography from a year ago, and everything in between. I was fascinated by the diversity – landscapes, portraits, still lifes, reportage from all the great photographers. And they were not expensive. I recently found seven photographic catalogues for $20 on eBay – about 700 total pages of tremendous, beautiful, diverse photography. You can find lots of wonderful inspiration in there. I strongly recommend looking through as many as you can lay your hands on.

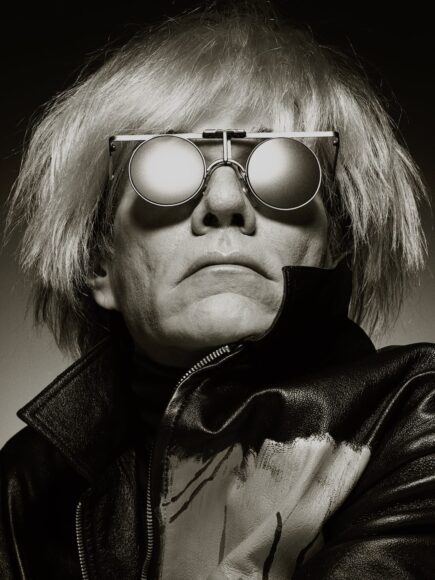

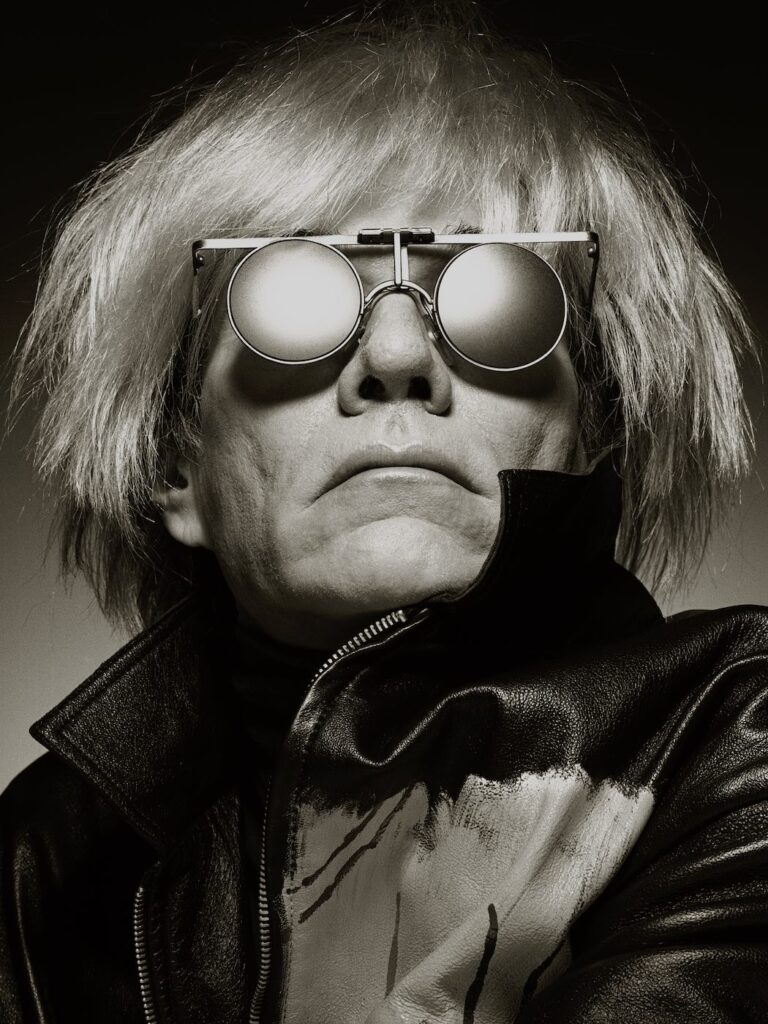

In my apartment in New York, there are four libraries of books. I like to surround myself not just with photography books, but with books on modern art, Pop art, Andy Warhol, ancient Japanese art, Vincent van Gogh, Jeff Koons. I can get just as much inspiration from a book about painting as I can from a photography book. I also enjoy reading biographies: my favourite is Henri Troyat’s Catherine the Great (1977). I have fashion books, too, but I’m not a big fan of coffee-table books. I prefer the fashion magazines, but I get so many of them that I have to get rid of them. That’s the nature of fashion, after all: you throw it out and move on to the next thing.

Learning photography is like learning to drive a car: the first time you get in a car, you think, I’ll never manage this, I’m going to kill somebody. I’m going to hit a wall, or, even worse, kill myself. And, after a week of lessons, you feel a little bit better about things. Then, let’s go as far as two years later, you begin to drive almost automatically. You get into a car and you automatically turn it on, change gears, look in the mirror. Once you get over the hurdle of technical things in a car, you’ve learned to drive it. I like to use that as an analogy for photography. You learn to drive the camera, really know the camera inside out, study different kinds of lighting and under- stand what each can give you, and, when you’ve learned all of that, it opens doors creatively.

I know that some photographers have a very hard time with the technical, and I commiserate with them. It was a real slog for me in the beginning too. To photographers who don’t enjoy the technical side, I often say that they have an advantage, because all of your concentration goes into the imagery.

Once you’ve learned to drive the car, however, it’s not how you drive it, but where you take it. The same thing should be applied to a camera. Get all the technical things in your back pocket so you can use them, but don’t let those be the driving force. Do not spend hours and hours, and days and days, looking at magazines for the latest lenses, the latest cameras, the latest software programs. Try to keep that on the back burner. Learn to drive the camera, and think about where you’re going to go with it.

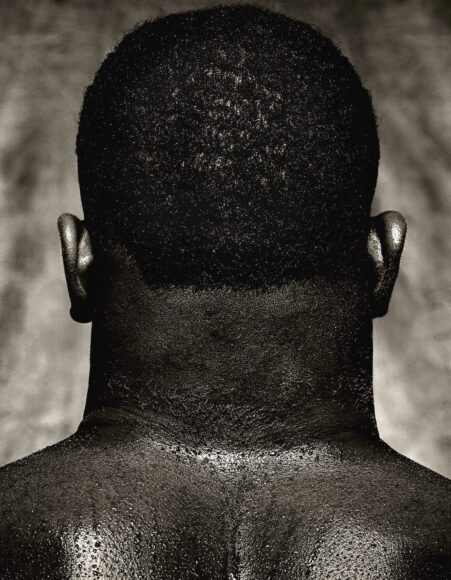

I did a shoot with a young Mike Tyson in the Catskill Mountains, in New York State. He was up and coming at that point, but he was clearly going to become an important fighter. I had already photographed a lot of good fighters, including Evander Holyfield, and I had this idea to do a boxer from the back. My father was a boxer, and he always said the strength of a really good boxer is in his neck. If you have a weak neck, you’re a weak boxer, and if you have a strong neck, there’s a chance you can survive a punch. I had Mike Tyson work out for about fifteen minutes before I photographed him, so you can see the sweat beads on him.

Like the one of Jack Nicholson, this shot was made with a Hassel- blad, but using a simple, on-axis strobe right above the lens. I didn’t use lights to either side of Tyson, but there’s one light on a canvas behind him, just to give him some vibrancy. So, it’s two lights – very, very simple. Of course, I did a portrait of Mike Tyson from the front as well, but this back shot was more unusual. I had always wanted to do a shot of a boxer from the back, where you could almost recognize who it was. And there were a lot of people who looked at that shot and said, ‘Is that Mike Tyson?’ So, that was a success.

So, once again: preparation, preparation, preparation. Just think- ing about what you might do. Have a plan before you go into a shoot. Especially with a celebrity. Really familiarize yourself with their work beforehand. If you understand their work, you’ll make a better photograph, and you’ll also know when to seize the moment and alter your plan – as I did with Jack Nicholson in the snow storm. If I hadn’t watched The Shining in preparation, I would never have thought of that shot.

I have a great love of strobes, tungsten light and HMI lights but, every so often, I have a mad kind of love affair with natural light. I did a lot of my early work with natural light,

but I only began to reconsider using it at the end of the 1980s.

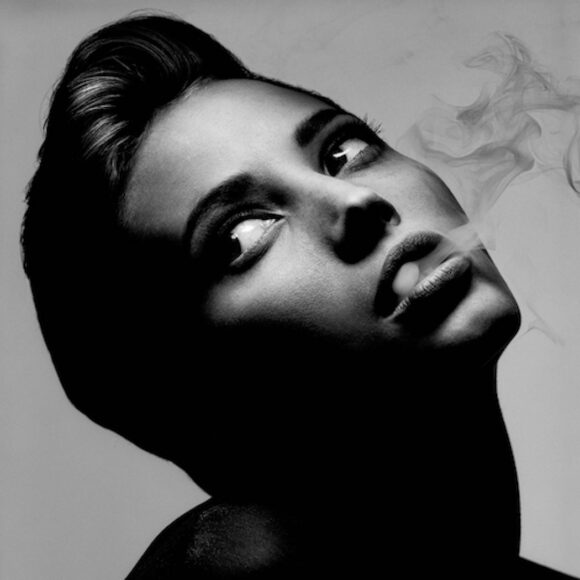

In 1993, I did a shoot for a whole day with Kate Moss under natural light, at times with just a little bit of strobe. It was the only time I ever worked with her, and it made for some amaz- ing pictures. We did the shoot in a villa in Morocco called Dar Tamsna. She was an up-and-coming model at the time and flew down from London. It was for German Vogue, and they wanted it all to be beauty and skin-orientated. We started the day at 7.30 a.m. and worked until 10 p.m. At the very end, she told me it was her nineteenth birthday that day.

For one shot, we had a local henna artist come in, who painted a tattoo on to the palm of Moss’s hand. She held it up to her face to show me the tattoo, and I devised the shot from what she had given me. I used a very simple, clean light. It was sunlight. She just closed her eyes to the mid-afternoon sun. (Later, when I processed that shot, I decided that it would be a good candidate for solarization – reversing the tones through overexposure, which has the effect of a print that looks like a negative image.) We worked all day with natural light. When the sun went down, I built a small studio indoors and I shot her with a strobe light against a canvas.

When you work with natural light, you have to ask yourself how best to use it. How could I shape it? How could I cancel some of the effects of the light? How could I increase light? How could I manage to work with it? Or how, sometimes, not to work with it at all, but just go ahead and shoot what is right in front of me? You should be thinking about the time of day you’re going to shoot. You want the light not to be sitting right on the horizon line, because it gets too chalky. If you want to shoot at sunset, you might want to start an hour earlier, so you work with the light as it changes. It’s an aware- ness of what’s going on, thinking about what the light is doing, and really looking.

Photographers sometimes become obsessed

by the camera and what they’re photographing, and they forget to think about what’s going on with the light. When you work with natural light, it changes and moves. You have clouds coming over, you have sun. You sometimes get lucky with a cloudy day with flat light. Natural light has its own beauty.

In order to make the most of natural light in my photographs, whenever possible I travel with a minimum of four 8-by-4-feet boards, black on one side and white on the other. I find these invaluable, because you can create shadows with them, block light with them. You can put them in front of a subject to bounce light up on to them, or if there’s a white cement ground and you don’t want all of that light bouncing up, you can flip the boards and make a black ground. If you’ve got a vehicle to carry them, they’re really fantastic. I can do whole shoots with just these boards and no additional lights.

So, with natural light, you really have to learn to capture it and try to control it, in a way. Whether using boards or thinking more about the time of day and the position of the sun, paying close attention to how natural light works in your shots outdoors is just as important as how you set up lights in the studio.

Most of the time, in the studio, I use a lot of expensive lighting equipment, sometimes $70,000 worth of lights, but you can also get a decent portrait using just two

$10 bulbs, one on either side of the subject, just above the head. When you use bulbs like this, it’s obviously really high contrast, so you end up with a dramatic shot. You can soften the light a bit by using flags – black squares of stretched fabric or even just black cardboard – in order to block some of the light from the bulbs. If you move the bulb around, you can see how much the light changes the way a face looks and the shadows it creates. It’s a corny expression, but you are painting with light. You can create strange, unusual shapes with just these two $10 bulbs.

Of course, there are limitations to this method. Your light sen- sitivity (ISO) has to be very high, 1600 or 3200 even. You’re increasing the ISO, because you have no shutter speed to work with, whereas the great advantage of an extremely intense light, like a strobe, is that you have shutter speed, greater depth and greater power. But working with two bulbs in this way provides an important learning experience and can teach you how to work later with a strobe. You can produce a whole portfolio of work with just the two $10 bulbs. There are limitations, but it’s a great, simple way to get started.