Robert Bösch creates magical images of a soberly seen reality – his motifs are shown in their very existence, without photo-technical manipulation or post-processing; without emphasis or pathos. Essential to the creation of his pictures is the choice of detail, such as the flank of a mountain or the incidence of light on a forest slope. The mountaineer and documentary photographer Robert Bösch certainly has this other side, which manifests itself even more clearly in the publication “Engiadina” than in all his previous art books.

Photographer and mountain guide Robert Bösch has been a freelance photographer in the mountains for over 40 years. Having shot for Stern, Geo and NatGeo, his travels and expeditions have crossed seven continents, including an assignment up Everest. An Ambassador for Nikon, Bösch’s work has been shown in galleries and museums but recently his focus has been publishing his art photography. His last published books – ‘Mountains’, ‘No Man’s Land’, and ‘Engiadina – are devoted to classic photography, which he feels connected to and which shapes his work.

READ THE FEATURE HERE IN THE ALPINE EDITION

WHERE THE GODS ROTATE VALLEYS

“Down with the Alps, clear view of the Mediterranean!” – this ultimate demand of the politically turbulent 1980s was certainly not created in the Engadin. The mountains don’t get in the way “up there;” they neither obstruct the view into the distance nor do they block the sight of anything else. On the contrary: they guide your gaze across an open, serene lake landscape to the horizon at the end of this beautiful world, where the gently sloping mountainsides from the left and from the right meet in the wide valley area of Maloja. Exactly where the sun sets on the shortest days of the year, as if the good Lord had rotated the valley until it was just right.

In this high valley, everything is a little lovelier than elsewhere – nature that can be enjoyed, sensed and felt. Skiing, golfing, kiting, surfing, cross-country skiing, mountaineering, biking, hiking, yoga, readings and concerts in the light mountain forest: nature is the visitor’s friend in the Engadin. Here, you won’t find deep valleys with raging mountain streams, wedged between steep and high mountainsides, or cold and barren high plateaus battered by the wind, demanding everything from man and beast in order to survive. Here, no masses of ice and rock clinging high up on the steep flanks threaten life on the small alpine meadows on terraced slopes or at the bottom of the valley. No – instead, it is simply the most beautiful and lovely thing that a mountain range can offer to people accustomed to civilisation. Here, you can feel the power of the mountains in the most pleasant way – without risk or danger.

Piz Roseg Schneekuppe, Bernina Gebiet, Engadin, Graubünden, Schweiz

When you hike into the Val Roseg or get off the cable car on the Diavolezza, you are on the threshold, so to speak, of the high mountains – where, according to Peter Handke, the pupils dilate – not because you’re confronted with an overpowering and oppressive mountain world, but on the contrary: sitting on the terrace of the Tschierva Hut, seemingly in the middle of the high mountains, surrounded by the glaciers of the Tschierva basin with the high alpine skyline from Piz Bernina to Piz Scerscen to Piz Roseg, one is at the same time an appreciative and distanced observer. This triumvirate of peaks forms a horseshoe, but how far away it is from the other, the world-famous ‘horseshoe’ of the three Himalayan giants Everest – Lhotse – Nuptse! There, at Camp II, in the Valley of Silence, above the Khumbu Icefall at 6,400 metres, you don’t sit on the stands and admire what is being offered at a safe distance on the alpine stage. Surrounded by the highest mountains in the world, which almost crush you with their 2,000-metre- high walls rising steeply into the infinity of the sky, you find yourself in the middle of it all, small, tiny and defenceless. How much more relaxed it feels here, on the sun terrace of the SAC hut with coffee, cake and beer. The Engadin is not the Himalayas – and not Patagonia and not Antarctica – but it has picked out the most beautiful and pleasant of all these landscapes for itself, so to speak.

I have known the Engadin for a long time. Already as a young mountaineer – before I got to know other, bigger and wilder mountains of the world – I travelled countless times in the Bernina area and in the Bergell. I have climbed most of the mountains depicted in this book. On the most diverse routes, in winter, in summer, in the most diverse conditions, deep snow in stormy weather or glorious sunshine. It always feels like coming home when, after the Julier Pass, at the end of the long straight, the Piz Bernina with the Bianco ridge appears on the southern horizon. The bluish shimmering ice on the west face betrays high winter conditions: cold, brittle ice that splinters like glass when you try to hammer the ice axe into it. It will be cold up there, the snow plume at the summit betrays the icy storm. I reflexively look at mountains through the eyes of a mountaineer: ice and snow conditions, avalanche cracks, biting wind or warming rays of sun. But the same eyes also see the beauty of the mountains, the deep blue of Lake Sils, the golden larches and above them the broad, freshly snowed peak of the Margna shining in the purest white.

Piz Bernina, Piz Scerscen, Piz Roseg (vlnr); Piz Corvatsch, Engadin, Graubünden, Schweiz

But I also see the world differently, with other eyes, with the eyes of the photographer. That is a very different view. I have tried to approach the Engadin with this other view. I’m glad I didn’t tackle this book project earlier, because I had been carrying the idea around with me for years. But only in the last few years have I understood that the project has a big problem: the Engadin is actually too beautiful to be photographed.

The Engadin is an alpine-landscape cliché, formed over thousands of years from stone, air, water, ice and light. And that’s not what I wanted to show with my pictures. For me, photography has to go beyond what I see, what is simply beautiful, what I can also capture with my mobile phone. For me, photography means creating images that only come into being through me, through my camera, through the detail and moment I have determined. Images that you don’t usually see when you look at the world. Like a painting: Segantini looked over the easel with its empty canvas into a landscape where everything could be seen, he looked into the everything of the Engadin mountains. What he saw was not yet a picture. Only when he forced his gaze, his decision to crop, into a square with brush and paint – forever, so to speak – only then did everything become a picture.

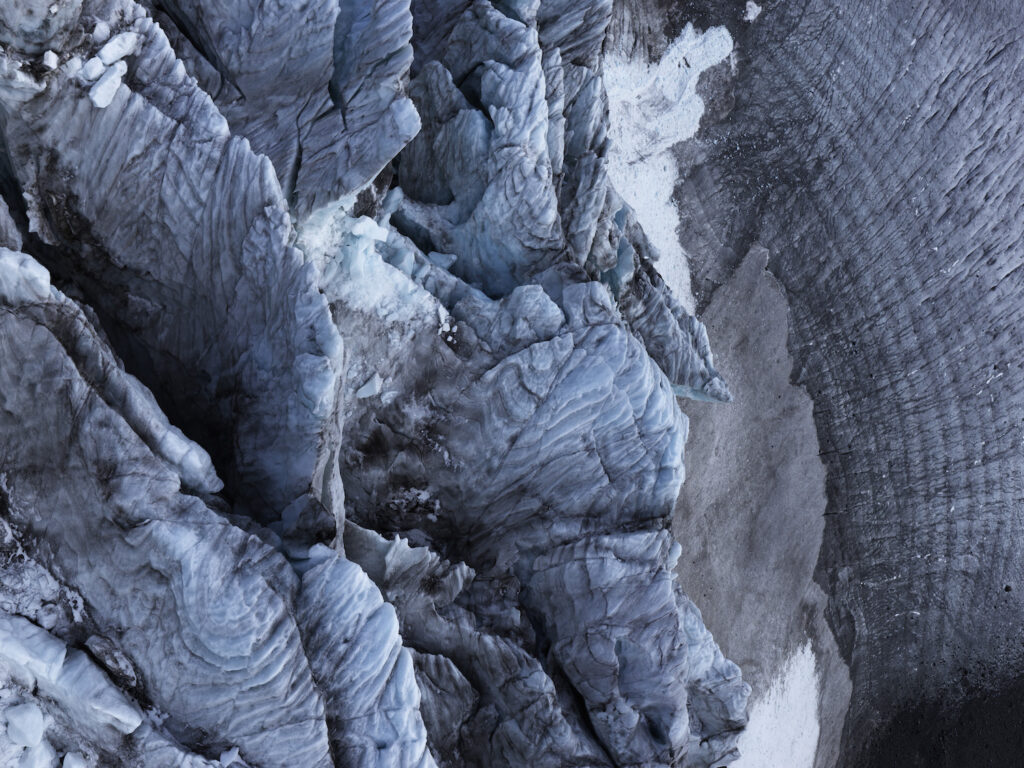

In my search for something new, I discovered something that I had known for a long time but had not perceived as new. The larches, for example. Not the autumnal golden ones – no – the naked, wintry larches. Sometimes perfectly symmetrical, sometimes wonderfully abstract skeletons, graphics like Giacometti sculptures sketched with a pencil. Or the late summer glaciers, the dying ones. Even in their inexorable disappearance, these ice monsters are beautiful elements of the high mountain landscape. Naked, stripped of the last old snow, washed away by heavy rain, ogives and medial moraines tell of the constant flow of ice, a movement imperceptible to the human eye. Dead, cold material that is seemingly alive, that is always in motion within itself and that, as a total mass, advances further into the valley over longer climatic periods or retreats to higher, colder elevations, or dissolves completely. One would not like to imagine the Bernina mountains in summer without glaciers. But it will probably become reality: not even the eternal ice is forever. At some point, the glaciers will return and fill the wide high valley and its lovely lakes with their icy masses again. We will not live to see it.

My last book, “No Man’s Land”, contained pictures I saw while travelling on this planet, but this book shows pictures that were taken while travelling in the Engadin. I didn’t aim to show what the Engadin looks like. I never thought about which views I absolutely had to capture – the sunset from Muottas Muragl, the first rays of sun on Piz Palü, the blue hours on the Tschierva glacier or the golden larches of autumn. That didn’t interest me. I wanted to show pictures that I had discovered, and which only came into existence through my camera. Pictures that – at least I hope – reflect as a whole the atmosphere of this unique mountain landscape.

The glaciers are retreating, the handholds are getting smaller, the mountains higher – everything is in flux, nothing stays as it is. I know that at some point even the not-so-high peaks of the Bernina will be too high for me. What remains are the memories of experiences and the joy of looking and searching for pictures.

ENGIADINA – THE VALLEY OF THE LARCHES

Doctor of Philosophy and art historian Angelika Affentranger-Kirchrath has worked as an art critic and curator, in particular for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. She has published numerous articles in specialized journals as well as monographs of artists of the 20th and 21st centuries.

What a blue! A sky blue? An azure blue? Certainly, but much more and quite different. It is a loud, piercing blue, a fanfare of blue. A blue that stores the southern light, is dazzlingly full of it, but which also contains a touch of the coolness of the northern light. It is a light blue, and yet not permeable to the gaze. It is the blue of the Engadin sky. Only in the Engadin does the sky have this beguiling colour.

Since time immemorial, thinkers, poets and artists have gathered beneath this blue canopy. It has stimulated them and, like Friedrich Nietzsche, inspired them to intellectual and poetic excellence. Only here did he feel completely healthy. Freed from the burden of everyday life and his migraines, he could work undisturbed in Sils in his sparsely furnished house not far from the lake. Thomas Mann also experienced rare moments of happiness in the Upper Engadin. Artists such as Ferdinand Hodler, Giovanni Segantini and Giovanni Giacometti, and the much younger Gerhard Richter, went in search of light and inspiration for their paintings in this region. Rainer Maria Rilke, on the other hand, could not stand the abundance of brightness and the proximity of the mountains in the Upper Engadin. He fled to Soglio in the Bergell with its somewhat milder light.

Engadin, Graubünden, Schweiz; Herbst, Lärche,

Robert Bösch is not afraid of the intensity of the Engadin light and the grandiosity of the nearby mountains. Even as a young mountaineer, he was often in the Engadin and for years now has been spending a lot of time at his home in Maloja, from where he has roamed the area and climbed many mountain peaks. Now, having travelled all over the world and collected images everywhere, he is dedicating a book to the Engadin with haunting photographic images that bear witness to his sensitive and personal dialogue with the valley.

The art photographer acts like a director who allows his protagonists to make their appearance: at times they take up the foreground as the main actors, at others they assume a supporting role in the background. Together they play out the drama of nature. At the beginning of the book, the Engadin blue stretches out as if a curtain were being raised. It forms the backdrop for a larch that stands out, glowing orange-yellow against the monochrome background of the sky. The larch is the protagonist in this book. For Robert Bösch, the Engadin is less the “valley of the Inn” than the “valley of the larch”. He has discovered it as his changeable model. When it first appears, it has been moved to the left edge of the picture and cropped, thus depriving it of its radiance. It is as if the photographer wants to tell us with this compositional decision: nothing that follows is as beautiful or strongly coloured as this shot. Robert Bösch is not looking for the perfect and interchangeable beauty of calendar pictures. He is not attracted by that which is eye-catching, but by what emerges when we do not look for it, by what reveals itself to the alert eye as an image in passing, something that we glance only once in this way. Moments of pause. “Moments” 1.

And so the strong Engadin blue soon recedes. It gives way to a sky in subtle shades of grey, a kind of vibrating veil, a membrane. And once again larches push their way into the picture. This time it is two trees standing close together on the right of the picture. The golden yellow of their autumnal needles has given way to the dark structure of their winter-bare branches. They no longer paint the background, they draw it with their black trunks and branches like bars and lines against a light background.

We encounter the larch like a refrain in this book. Only rarely does it appear alone, as an individual. Mostly it stands together with many others, as part of a forest. Seen from above from a helicopter, the trees now seem small and fragile like matches. Explored from inside the forest, the individual tree loses its contours, the snow-covered forest becomes impenetrable to the eye.

And again and again, it is the larch that connects below and above in this book and brings together what is known, tangible and experiential on Earth with that which can only be imagined: the shimmer on a glacier ridge and the impenetrable blue of the Engadin sky.