Restomod – Celebrate the Past, Embrace the Future

There’s something of a ruckus going on in classic car circles at the moment. There’s a growing breed of restorers who, rather than returning vehicles to their former glory, are daring to try to improve them and add modernity of design and technology. Are these restomods (restored and modified) destroying heritage or making icons more usable and relevant in today’s automotive landscape?

The last 12 to18 months have been memorable and forgettable in equal amounts. In amongst the on-off restrictions of lockdowns and the uncertainties surrounding vaccine roll outs, there have been some economic success stories. Some obvious customer commodities have seen unprecedented growth – from TV subscription services and electronic communications to fitness equipment and coffee subscriptions. One slightly surprising winner has been the classic car market.

Whereas the true economic reality may be slightly more complicated, there are some simple underlying human behaviours at play. People have had a lot more time on their hands, reconnected with themselves, and are suddenly bereft of the opportunity to splash thousands of pounds on foreign holidays – and hence have newly identified disposable incomes. The value of sales has increased, as has the number of sales.

Classic cars can fall into different categories – from the factory-fresh exotica, rarified atmosphere of unadulterated limited edition specials (a 240 mile McLaren F1 going under the hammer in August, if you have very deep pockets) to the ‘spares or repair’ classified staple (believe me, they are spares at best, and there is a reason why someone left them in a barn for you to ‘find’).

Between these lie an intriguing middle ground of automotive history that should be celebrated and enjoyed. Whether this consists of earlier missed investments, a dream car of youth, or a nostalgic memory that needs to be re-lived.

I have loved cars for as long as I can remember. I have loved them for their design, for their engineering marvel, and for what they enable people to do. Whatever your own reason for admiring classic cars, there are some facts that should be recognised. In general, old cars weren’t that good. We hark back to an era where things were different, when roads were empty and driving was a pleasure and a skill.

The driving environment has changed almost beyond recognition over the last 60 years since the first English motorway came into existence (oddly entitled the ‘M6’ due to a quirk in UK road labelling). The effortless road trips that were only punctuated by a picturesque picnic stop to rejuvenate passengers and fuel loads have been replaced by stop-go traffic and a war of attrition with Chelsea tractors for valuable tarmac space.

When I learned to drive, the Highway Code was to be memorised, the back page consisted of the stopping distances of vehicles at varying speeds. Without many exceptions, here lies an issue: your average 1960s design icon cannot stop anywhere near as quickly as the latest entry level city car. Bumper technology advancements also mean that, when the relative stopping distances reach their unfortunate overlap, the newer model will fare significantly better.

Environmental issues and emissions standards have only recently pushed technology to a point where energy can be extracted from fossil fuels efficiently and relatively cleanly. One reason old cars have that distinct smell is a by-product of less-than-ideal tailpipe gases. Crumple zones weren’t a thing, nor was ABS or cruise control and, until Volvo did us all a favour in the 1960s and gave us the 3-point safety belt, we were all fair game.

During the development process cars are created by a group of enthusiastic experts to serve a purpose. Whether that purpose is to retrieve the latest purchase from your favourite Swedish furniture emporium, or to deliver physics-challenging lap times round race circuits is immaterial. Despite their technology limitations classic cars were built for a purpose and that purpose is still relevant today.

Enjoyable as it is watching race series like Goodwood Revival, it fills me with dread at the same time. These are priceless pieces of automotive history being pushed to and beyond their limits. Once driver skill or traction limits are exceeded, the pain is emotional and physical. Cars crash. Parts are replaced.

When you see pristine vehicles that have gone through ‘nut and bolt restoration’ the attention to detail can be phenomenal. In many cases, the quality exceeds that of the original car. There is a reason for this: it is better than the original! Parts are replaced often with those that have undergone manufacturing and treatment processes that didn’t exist when the car was first conceptualised. I urge you to watch an engine rebuild (probably on time lapse as it is a lengthy process) all major components are rejuvenated, replaced, revised… changed. There comes a time where Trigger’s broom concept raises its head: if you replace the handle, still the same broom, replace the head, still the same broom – however nothing is original.

At what point is a car classed as ‘original’? Even the concept of ‘matching numbers’ means that people have only ensured that the replacement parts are of the same period, even if they are not the original parts.

An analogy can be made with aesthetic surgery – this is the nip and tuck of the automotive world. Small little updates here and there to keep things looking, feeling and working a little bit better than if left to the natural ageing process. Some procedures are subtle, unnoticeable to the untrained eye; others obvious, but understandable and appreciated. The analogy can go further in that some features should be left to age naturally and some alterations can be detrimental rather than enhancing.

The renowned automotive designer Frank Stevenson was given the challenge of bringing the iconic Issigonis designed Mini into the twentieth century. The process he undertook involved reimagining the vehicle across the decades of design – the 70s, 80s, 90s. Without doubt, the vehicle looked incredible and time-period correct in each iteration. What that suggests is that you can retain the design ethos, yet make it relevant in a more modern setting.

Alfa Romeos hold a special place in the heart of anyone with an automotive passion. Their stunning designs have often been let down by some dubious build qualities and their affinity to oxidisation. Alfaholics have been modernising the design and making the technology fit for purpose for a number of years. Their following is growing rapidly as is the value of the products they make. The price tags of £300k-plus become uncomfortably acceptable when you consider each demanded 3,000 hours of work, and this is not minimum wage skill set.

How much of the car is sacred? The sound and smell are an intrinsic part of the product. Replacing the engine, therefore, is significantly more intrusive than a change of body colour. Emissions regulations have led to incredible advances in technology eking out ever more performance from those dead dinosaurs. Comparing what is possible today from a 1.6 litre engine versus what was possible when an Opel Manta was first created, puts them not even in the same game, let alone the same ballpark.

There are lines that need to be drawn. The sound of an air cooled 911, a four cylinder boxer engine or a perfectly tuned V12 cannot be beaten in the automotive world, in my view. Sounds that you hear coming from a distance which make you stop mid-conversation to see which legend you are just about to be honoured with.

The Volvo P1800 is an absolute stunner, but the performance let it down and the limited 1.8 or 2.0L engines (100 and 130hp respectively) put it in the ‘all show, no go’ category. Cyan came along and, with a history of race preparing Volvos, performed their precision surgery with some adept weight loss and implanting a 2.0L 414hp engine to create a £350k vehicle that has the critics singing its praises.

Electric vehicles are all the rage at the moment, with every major manufacturer jumping on the bandwagon of environmental superiority. Whereas the claim would be that this is the ‘right thing to do’, there are moves afoot to limit the usage of traditionally engined vehicles. This means that before too long the sounds of V8s will no longer reverberate round the enclosed streets of our beloved cities.

EVs are incredible. If you haven’t driven one yet I urge you to do so – you don’t even need the mind-warping performance of Tesla or Rimac, a Renault Zoe will equally convince you of the benefits. If governments are pushing us to ditch the internal combustion engine, the real world performance is as good if not better, and your kids will worship you for saving their dying planet, what’s not to like?

Does that mean we should be ripping out the engines of every vehicle ever created? Far from it. If the engine is merely a source of energy, we can go back to the medical analogy, do heart transplants change the person? Or is the engine more than a method of producing power and, in fact, akin to a personality transplant?

Where the engine is an intrinsic part of the car’s character can this be replaced? The thought of ripping out the glorious 6.1L V12 BMW engine from a McLaren F1 fills me with sadness, however, swapping out the gutless 2.8L V6 from the DeLorean seems perfectly acceptable. And that’s even without the concept of a working flux capacitor!

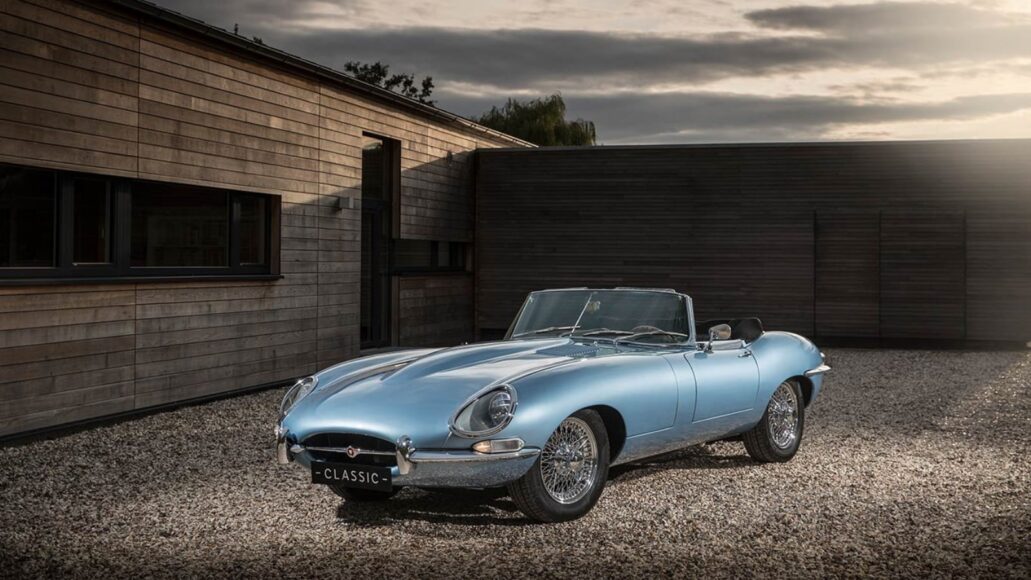

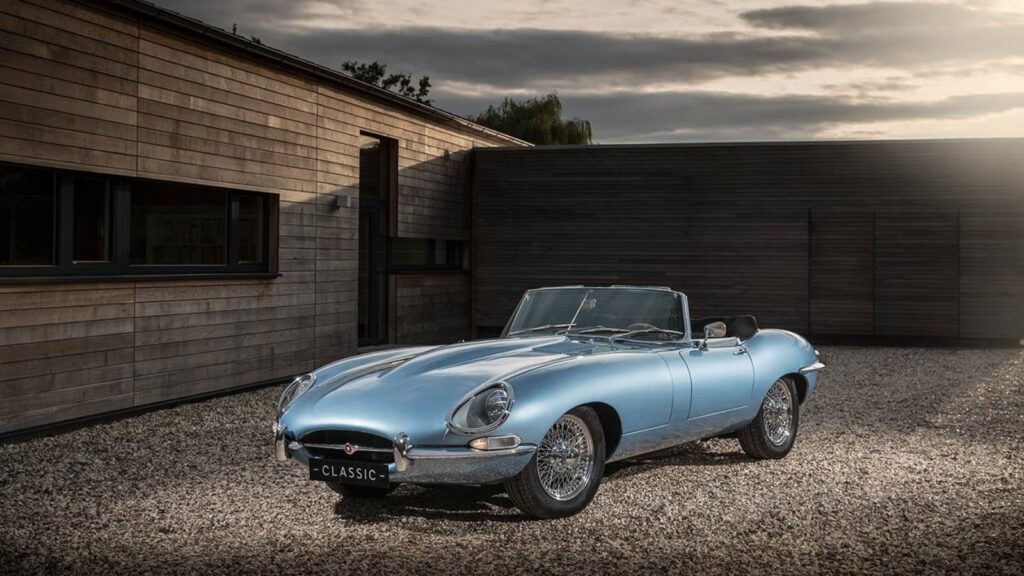

If a Jaguar E-Type V12 is untouchable, what about the lesser six cylinder? Jaguar themselves have offered an EV conversion from 2017, the Concept Zero. Where the original 3.8L car had a 0-60 time of 6.7s, the EV update does it in 5.5s. It has the 60s style, 21st century technology and won’t fall foul of the congestion charge or environmental protests.

This is no longer limited to the mad inventors and shed tinkerers, there are some serious investments and serious brands involved. Within the last months, David Beckham has put his financial clout and brand power behind Lunaz, a UK startup specialising in classic car revival. The company isn’t shy about choosing the best with electrified versions of Bentley, Rolls Royce and the Mk1 Range Rover.

If you are still in doubt about the seriousness of the movement, the London Classic Car show, returning after its Covid-enforced hiatus, has a dedicated theme regarding the electrification of the classics – let the cloth-capped debate ensue.

Cars of all varieties are being personalised at the point of sale. Everything from a unique sticker on your favourite Vauxhall all the way up to coloured carbon fibre on your chosen hypercar. After-market tuners will take whatever you have and tweak it further, extracting every ounce of performance of the hardware available. If after-market upgrades are acceptable to exceptional vehicles is there a time limit as to when those upgrades should be applied before it becomes unacceptable? Would exceeding that moment merely mean these restomods are just very late getting to the party?

It seems like, almost since its conception, people have been upgrading and improving the Land Rover Defender, yet this has never dented its appeal. Twisted, amongst others, operating out of its Yorkshire base for over 15 years, have been ‘re-engineering’ the classic Defender. As well as the common upgrades of chassis, brakes and interior, out goes the engine to be replaced by a better fuel consuming version or now even an electric version. For a vehicle that has morphed from a go-anywhere workhorse to a catwalk accessory, the ability to silently cruise the streets of London is an essential evolution.

Another automotive icon, the 911, has been successfully coiffured and pimped by Singer since 2009. Carbon fibre replacing sheet metal, interiors redesigned and engines remapped. Singer haven’t progressed as far as EV installations yet, but Everati have done so. With Porsche themselves admitting that the next 911 will have electric propulsion the brand enthusiasts shouldn’t get too worried about damage being done to the legacy. As well as the emotional angst no one should be worried about what these upstarts are doing to the residual values of their own investments – Singers change hands above £500k and there seems to be a new market for those ‘spares or repair’ body shells.

Sometimes the effort required to restore an original is more than it is to recreate from scratch. As such a number of ‘remastered’ classics now exist. These range from the OEM derived Aston Martin Goldfinger (glorious homage or cheap publicity stunt? You decide) to the Jaguar Concept Zero to companies who specialise in new ‘old’ cars. For the fans of English classics, we have recently seen David Brown with recreations of the Mini and the DB5 and RBW with an EV MGB. Charge Cars have completely reinvented the benchmark American muscle car, the Mustang, as an EV for the twenty-first century. If Italian thoroughbreds are your thing, then how about an MAT Stratos – provide your own donor vehicle and a starting price £500k and a legend remastered for today’s roads can be yours.

In my mind, classic cars should be appreciated as works of art and engineering inventiveness, and be retained as a living history lesson for those of us not lucky enough to enjoy them the first time round. However, they should be enjoyed by as many as possible. Retain what makes them unique and special, but don’t shy away from recognising their shortfalls and demanding better.