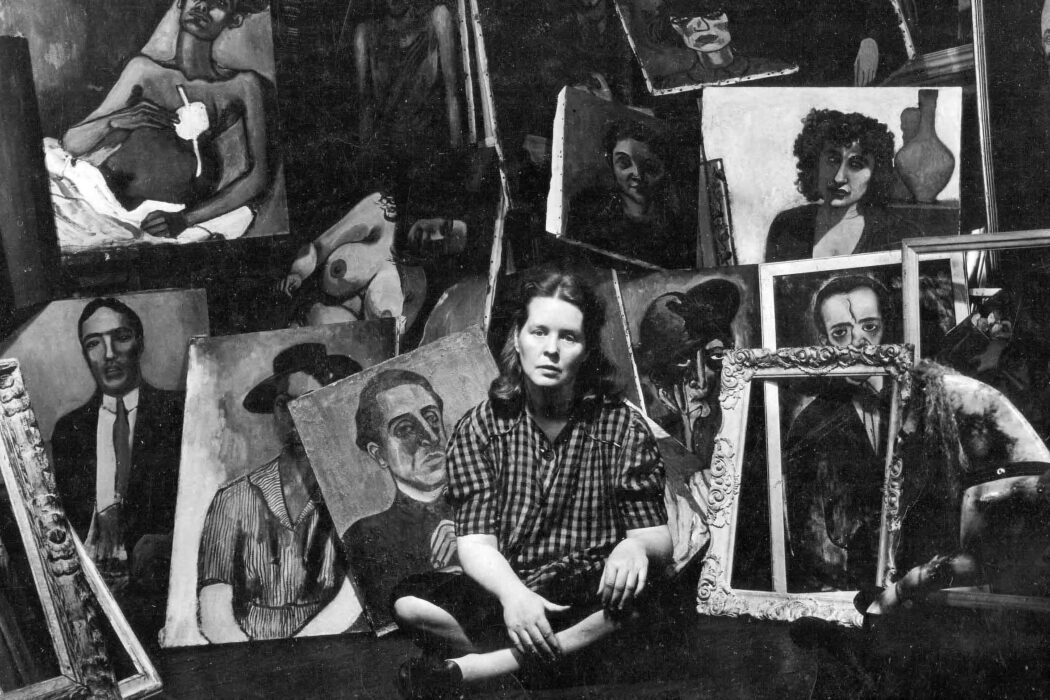

Alice Neel (1900-1984). An exhibition detailing a lifetime of work of an artist unflinching in her connection to painting and capturing the life-essence of those she chose as her sitters.

From 16 Feb to 23 May 2023 the Barbican gallery welcomes Alice Neel, the foremost painter and, in her own words, ‘anarchic humanist’ to their programme in her largest UK exhibition to date. Curated by Eleanor Nairne, the exhibition takes us through Neel’s life and work in chronological order, from her birth in 1900 in rural Pennsylvania to her final years in 1980’s New York at the height of her fame, passing through the changing political and social landscape of America in the 20th century.

READ THE FEATURE IN THE ALICIA AGNESON EDITION HERE

The story told is one of deep love and deep loss. Losing people she loved, Neel faced heartbreak through experiencing the death of her first-born child to then losing her husband, Cuban artist Carlos Enríquez Gómez, who fled to Havana with their second child in the late 1920s. It is these stories interwoven through the exhibition’s chronology that gives the sense that Neel knew suffering.

Unshy to the injustices of life, Neel painted stories through the people living them. She felt instinctively from an early age that art was her calling and found herself depicting scenes of Havana and its people in her formative years as a painter. After a painful and traumatic entry to young family life, Neel spent time in various psychiatric hospitals whilst she aimed to process the psychological turmoil of her early adulthood. During this time, painting became her life blood, strengthening her will to survive.

Living in New York’s Greenwich Village and a new chapter beginning, her work ventured into the peculiar and often surreal depictions of lovers and friends to paintings capturing the blazon realities of political America. In one room her closest friends and lovers are shown in nude abandon. Multiple penises are crafted on the body of one man with a slight expression of mania to his face, as one might expect of a character which elicited a numerous-phallic representation from an experimental Neel at the time.

It was during this period that she gained employment through the Public Works of Art Project, which was launched by the government to improve widespread unemployment and poverty after the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Receiving a wage for her work, she painted moments of conflict and protest in New York City – immortalising those fighting for a voice was a subject matter close to her heart. In one work titled, ‘Uneeda Biscuit Strike, 1936’ we see the chaos of men and women fleeing police on horseback as the tiny figures of small children stand in witness next to their mothers clutching babes in arms, the backs of their vibrant red and green coats popping against the sombre tones of the ensuing action. Was Neel drawn to capturing the gaze of the innocent child owing to an acute awareness of a child’s fragility?

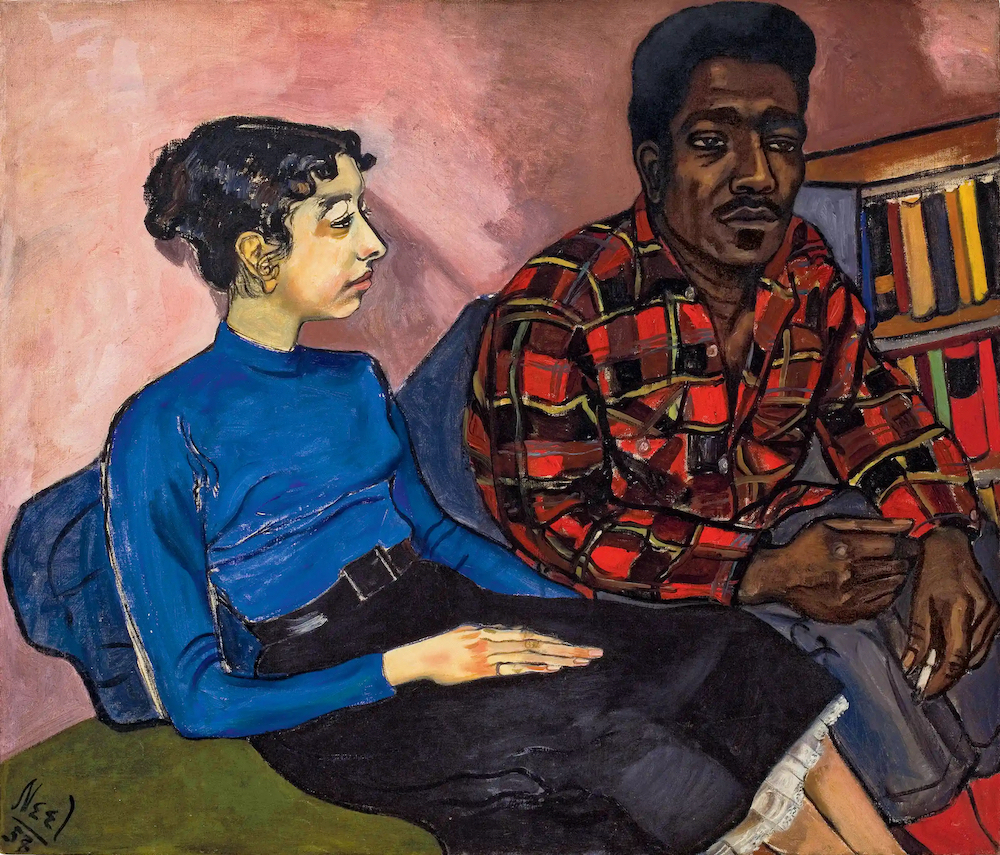

A resident of Spanish Harlem in the 1940s, Neel’s work paid attention to the lives of mothers and children in her community. A single mother again herself with her third child, son Richard, she then met Marxist filmmaker Sam Brody who became father to her fourth child, son Hartley. It was during this time that her work started to take the form and style she has become most remembered for. Portraits of mothers and their children as well as political figures she admired, the distinctive bold, thick black lines structuring their figures, the form of them both strong and fragile in the contour of a singular stroke. Works such as ‘Black Spanish-American Family, 1950’ and ‘Georgie Arce No.2, 1955’, demonstrate this distinctive quality of her skill as a painter, later becoming a hallmark of her personal patent as an artist.

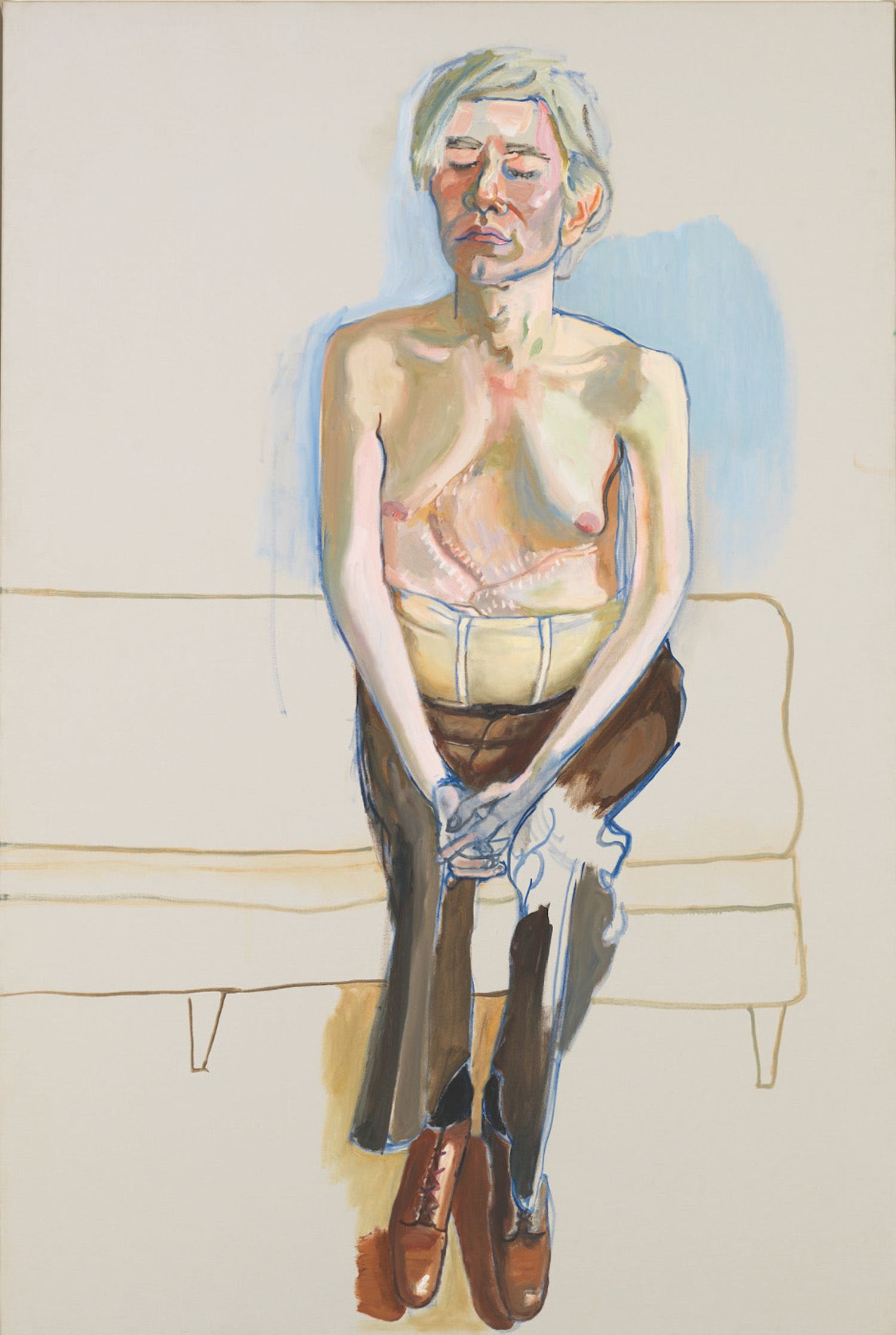

Never more apparent is this style than in the final rooms of the exhibition. Canvas after canvas one is met with gaze after gaze; a conveyor belt of the sitters she welcomed to the white and blue striped armchair of her apartment. To sit for her is a mission futile in fuelling ego. She became known not for the flattery she’d bestow her subjects. People of varying class, colour, wealth, sexuality, age, body-type and prominence are here. Even Andy Warhol, perhaps her most famous sitter, makes an appearance – here he is shown as vulnerable, as human and with scars on his torso, we seek a moment with him that is different to the image of the cool, almost caricatured man photographic history portrays. To have painted Warhol demonstrates the breadth of people she painted throughout her life. Just as she latterly painted those both famed and notorious, her belief was in the necessity to depict those who were not seen, to make visible the invisible both in body and feeling, ‘One of the primary motives of my work was to reveal the inequalities and pressures as shown in the psychology of the people I painted.’

Approaching her sixtieth year, Neel sought therapy for the first time in her life. It was then that she raised the personal courage to approach the curator of the Museum of Modern Art at the time, Frank O’Hara, curious to see where her work might land. Set against the rising second wave feminist movement the spotlight finally landed, and Neel was standing centre stage. In the final room of the Barbican’s extensive exhibition, we see and hear her speak in the 1978 film crafted by Nancy Baer titled, ‘Collector of Souls’ tracking Neel’s life and work. In a moment of commentary to her late in life success she replies to the interviewer, ‘Better late than never!’. It is this humour which punctuates throughout the suffering and injustice of human inequality she chose to depict throughout her life’s work.

Returning my thoughts to the school children I entered with, my mind wanders to the notion of her work commanding the attention of young and old today. The vast intersectional identities of her sitters standing proudly on the walls of the Barbican – inspirational markers of one woman’s commitment to capturing humanity as she uniquely encountered it. One might argue; is there a common sense among all of us which we feel links us intrinsically? How unique is Neel’s personal depiction of humanity, versus a common connection amongst us all on what it means to be human. She stated herself: ‘the best reason that people go into art and stick to it is because it’s essential to them feeling that they’re living’.

Existential questions abundantly raised? Perhaps, but take these with a pinch of salt. Neel certainly did.