“All hail The Datsuns, heroes of the New Rock Revolution,” read the front cover of NME in October, 2002. “The Datsuns are what the world needs,” proclaimed Dave Grohl. And so they descended, an antidote to a stagnating UK music scene, introducing a new generation of kids to no-nonsense rock and roll, alongside bands like The Strokes, The White Stripes, and The Libertines.

After a ferocious battle between record labels, The Datsuns finally signed an exclusive licensing deal with Richard Branson’s V2 for an unprecedented six-figure sum, going on to collect numerous best-thing-since-sliced-bread awards, and promoted heavily by such deejays as John Peel and Zane Lowe. But it wasn’t the records that people craved. The band had built its reputation on one thing alone: live shows. There isn’t a high-energy band that The Datsuns haven’t been compared to – Led Zeppelin, Deep Purple, T-Rex, The Stooges, AC/DC, The Ramones – and at the time, everybody wanted a piece of the action. One music executive went so far to say “I actually pity bands that have to support them or who they support. No one wants to go on before or after them.”

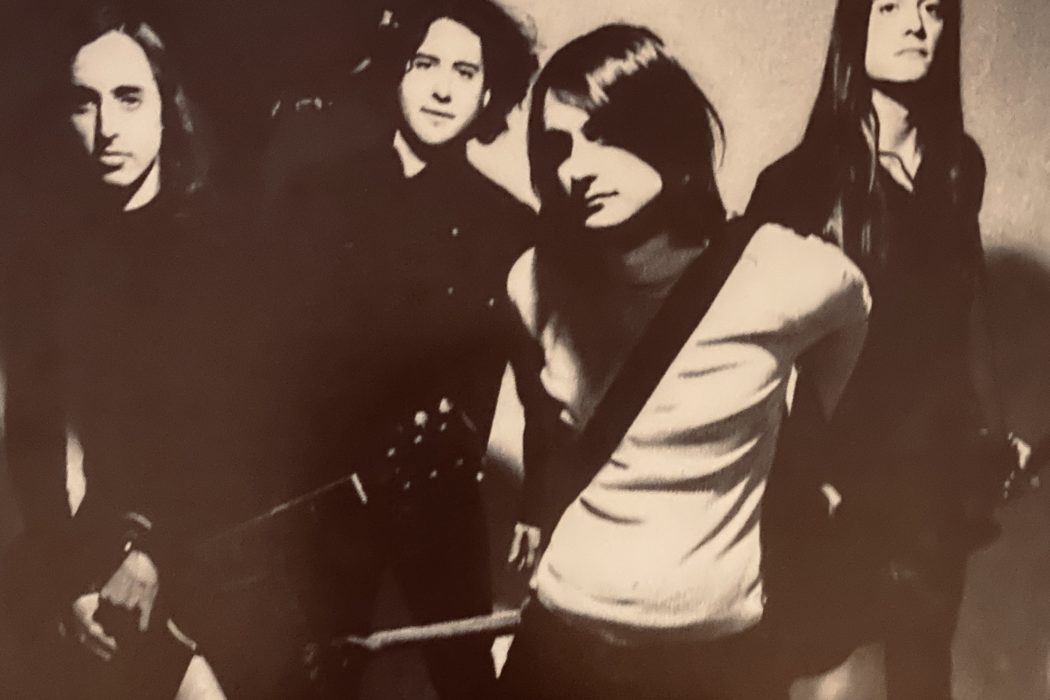

In their own words, The Datsuns are “Country boys from Cambridge, New Zealand, and we’d be stupid to think anything else.” They spent their late teens playing small gigs in New Zealand and Australia, winning Battle of the Bands competitions, and selling records on their own Hellsquad label. But it wasn’t long before Dolf de Borst (lead vocals, bass guitar), Christian Livingstone (lead guitar), Phil Somervell (rhythm guitar) and Matt Osment (drums) were thrust into the media spotlight, unleashing their own brand of retro rock on the UK charts.

But what goes up must come down.

Their sophomore effort, Outta Sight/Outta Mind (produced by Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones) received a critical backlash – a reaction predicted by the band on the penultimate track of their self-titled debut. Indeed, the lyrics to You Build Me Up To Bring Me Down are a scathing reminder of a fickle music press: Everywhere, even your home town / Finally decides you’ve made a sound / They turn their heads and stare at everything you got / And make you something you are not.

But The Datsuns were never in it for the fame: “We’re doing this because we love to do it. It’s what we get off on.” And now, ten years on, with new drummer Ben Cole in tow, they’ve unleashed their fifth album, Death Rattle Boogie, lauded for its idiomatic mix of heavy rock, psychedelia, guitar pop and blues.

How are you feeling about the new record?

It always takes me a little time. I need to get some space from a record before I start to like it, and this one is no different. We spent a lot longer making this one, so all those little hang ups you have, the things that annoy you, we had a chance to iron those out. But I am pretty happy with this one.

You’re all based across the world now. How long did the recording process take?

It took maybe a year, but we were all writing on our own and it was recorded over three or four sessions. We started at the beginning of 2011 at my studio here in Stockholm and we recorded fifteen or sixteen ideas. The original idea was to just record an album, but then everyone went back to their respective corners of the world – Christian to London, Phil to Auckland, and Ben to Wellington – and with that little bit of distance and time, it made us think ‘we can do better than this’.

We wanted to rerecord a few things and much of it was left half-finished, so it was up to me to finish on my own at my studio here – vocals, overdubs and things. I actually really hated doing that, because The Datsuns has always been a collective thing, a democracy, so it was really hard working alone. I would do vocals, send them across, wait for feedback, it was just a really tedious process.

I much prefer having everyone together and working straight on it. Later in the year, we got together in New Zealand for a short tour. Usually when we rehearse, we get really bored and have short attention spans, so we just start writing new things. And of course, everyone had been writing by themselves and new material had cropped up in the months in between, so we had a greater pool of songs to choose from in the end.

I heard you had forty or fifty ideas?

Yeah, basically, that’s why this record is the longest one. It’s fourteen songs, over fifty minutes, and that’s really because we couldn’t decide on what to choose. Everyone had their favourites and everyone had different favourites, so we all mutually agreed on seven or eight of the tracks, and the rest was ‘if you want that song, then I definitely want this song’. We just thought ‘fuck it’ and threw it all on.

Are songs that don’t make the final cut saved or forgotten about?

Ideas definitely stay around. There are some things on the record that didn’t feel super-finished, but everyone else was saying ‘it’s ready now, you need to leave it’. There’s a song called Brain Tonic, which is a slow guitar number, and I was really happy with the lyrics, but thought it could have used another part or something, but everyone was saying ‘leave it’. We then sent the record to our publishers and a week later they said ‘we really like this song and MTV want to use it’.

It’s nice to get other people’s perspective on things. You can really exist in your own little bubble of what you think is good. I really like that dynamic of The Datsuns. It can be really stressful when we’re in the studio. But at the same time, it’s always progressive.

There’s the cliché that all songs are like children. But is there one song on the album that you’re particularly glad you made, or perhaps didn’t expect to make?

There’s a song called Wander the Night. I never thought we would really do anything like that.

It reminds me of The Doors.

Yeah, a few people have said that. It’s not a super-conscious thing for me, because I don’t really listen to The Doors all that much, although I do have their records. That song was born maybe five years ago, just the basic idea on the organ and the chords. So, this demo had just been sitting around and I hadn’t shown it to anybody, and we had some free time at Roundhead Studios. We had worked on lots of different ideas and thought ‘we’ve got another three or four hours tonight, let’s just push record and see what happens’. So I said ‘I’ve got these chords, maybe we could try something in this vein. Just follow my voice like we do at rehearsals’ – because at rehearsals we spend a lot of time jamming, ad-libbing.

We just played the demo once, and the second take is what you hear on the record. I really enjoy making records like that. I think the next one will be much more spontaneous and ad-libbed – just push record and see what happens. Christian and Ben are really good musicians, it’s nice to let them fly and see what happens.

People always compare you to bands like Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, but are there any new influences that can be heard on the latest record?

We have been listening to a lot of heavy 70s psych and heavy boogie, pretty obscure stuff like Elias Hulk and The Groundhogs. It’s a similar thing to the classic 70s bands, but just a little less well known.

After self-producing your last two albums, what was it like working with a producer again?

Nicke Andersson [The Hellacopters and Imperial State Electric] co-produced everything we did in Sweden. The other stuff was just us. It was really fun. I mentioned before the dynamic of the four of us, and a lot of that is tension, compromising ideas, and we have to stand up to each other. It’s quite nice to have a fifth person to say ‘this is the best idea’, and they don’t really have a stake in it – they just want to make the best record that they can.

John Paul Jones, who produced your second album, Outta Sight/ Outta Mind, must have been one of your heroes. What was it like to work with him?

He’s a very genial, lovely fellow. We had a really good time. The whole thing was smooth, possibly too smooth. I could have been pushed a lot harder on a few things, but at the time it was enjoyable.

What are your thoughts on Outta Sight/Outta Mind, considering the backlash it received?

It’s kind of a cliché. We were expecting something along those lines anyway. I don’t listen to any of our records, but I really like a lot of the songs on that one. I feel we made really expensive demos with that record. For myself anyway, I feel I should have been more aware of what key we were doing some songs in, and been a bit more brutal about some of the things I was doing vocally. Once we’d finished the actual recording part, it was out of our hands, and we ended up remixing things quite a few times. The whole thing was like ‘okay, it’s done now – let’s get on with the next one’.

But are you happy with it still?

I’m not happy with any record! I always think ‘we should have done this or that’.

How has Ben’s drumming brought a new dynamic to the band? Would Death Rattle Boogie have been made without his influence?

Definitely not. Matt’s drumming was always perfect for the songs we were making, but Ben’s drumming is a lot more versatile, so if we try something outside the box, he’s totally capable of doing it. He studied drums at jazz school and he can basically play anything. You can see with every record, it’s still very much The Datsuns, but we push it a little further, try new things here and there.

Have you managed to gauge a reaction to the new album yet?

It’s been really positive. We haven’t put out a record in four years, and it always helps when people miss hearing something, so when they finally hear it, they think ‘wow, that’s the sound of the band I love’. The first two singles did that, but once you actually get into the record, there’s a lot more going on.

The band has assumed responsibility for the corporate side of things now. Has that been harder or easier?

There’s a lot less red tape and bullshit to go through. It’s like ‘we want this to happen now’ and it’s done. We have fewer resources to draw on, but at the same time it simplifies and streamlines the whole thing. We also don’t have to worry about stroking people’s egos to make them feel part of the project. Music is the same as business – you have business partners, for lack of a better term. A lot of the time, something will be the band’s idea, but you make it sound like it was this person’s idea, so they give one hundred percent to the project. It’s a bit unprofessional, but that’s just the way it is. If you’re doing it yourself, you know what the stakes are, and you know what the numbers are. It’s a lot more basic.

Any favourite UK venues?

We’ve played the Underworld about four or five times now. It’s not the biggest or smallest venue we’ve played in London, but every time we play there – there’s something about it, I don’t know what it is. Maybe it’s the way the stage and audience meet each other, it’s fantastic.

Will there be a Death Rattle Boogie tour?

Definitely, but we won’t be in the UK until the new year.