The story goes, after an all-conquering 1988/89 F1 season for McLaren the solitary blot on an impeccable record that was the loss to Ferrari in Italy frustrated the Technical Director, Gordon Murray, into action. At the airport on the way home, Murray pitched a plan to make a road car to the boss, Ron Dennis.

Using all of his engineering knowledge and lightweighting expertise, gathered from decades pushing the boundaries with F1, the road car would be aimed at being the closest thing to a race car legally permissible on the roads. Other people had converted race cars to be road legal but this was a completely different concept. Using race car mentality, materials and processes, Murray was able to design a car that completed a 0-60 sprint in 3.2 seconds and a published top speed of 240mph.

It is worth taking a moment to put that into context. Back in the 80s, when this car was conceptualised, for those of us with a mechanical leaning, the posters of dreams on the bedroom wall were of Lamborghini Countach and the Ferrari Testarossa. Eye-poppingly beautiful, unattainable, feats of engineering excellence, cars with off-the-scale performance, 0-60 times the good side of 6 seconds and top speeds at a dizzying 180mph.

Despite the appeal, and the now substantial financial gains owners have enjoyed, the F1 was not an instant success with some reports existing of cars being sold below list price and that the fabled 106 units took 6 years to sell. However, with a top speed record and a Le Mans victory later, a legend was born.

READ THE FULL ARTICLE HERE IN THE SPRING EDITION

The Le Mans victory remains unsurpassed as a motor sporting endeavour. McLaren won on its first outing, dominating the field, as it had done in that legendary 1988/89 F1 season, holding 4 out of the top 5 places. The top speed record was equally as impressive, a five year old prototype vehicle set out to ‘see what was possible’. What was possible was 240mph, some 23mph faster than the previous holder, the Jaguar XJ220.

Such was the car’s dominance over everything else, and the performance a step change from any other car in existence, lumping it together with others seemed disrespectful – a new product category, the hypercar, was created to stamp dominance over mere supercars.

Hypercars operate in a different universe to your standard sports cars or even supercars. They are categorised by mind-boggling performance figures, a purchase price that can easily surpass 7 figures, with some eye-wateringly beautiful and expensive options and a very limited customer list. Although some recognise the McLaren F1 as the first, the fact that McLaren wasn’t ‘a proper car company’ at the time (the existing McLaren Automotive only came about in 2010) allows some uncertainty about the title.

If a hypercar is seen as the pinnacle of corporate endeavour, where supercar manufacturers unleash their resources and engineering skills, then the car that took the speed record from McLaren, the Bugatti Veyron, could have a serious claim to the title of being first. Whoever you class as the inventor of the segment, the growth in participants has been increasing consistently for the last 25 years.

In car circles, people talk about the holy trinity of hypercars: McLaren P1, Ferrari La Ferrari and Porsche 918 – three superlative vehicles, created independently from each other, launched within a year of each other. Technology boundaries aren’t pushed, technology boundaries are redefined.

If the purpose of the hypercar is to redefine performance expectations, then we appear to be heading down a cul-de-sac; a road that has an end. No matter how inventive we humans are, we are bound by the laws of physics. The two main measures of performance are 0-60 times and top speed: acceleration, the indicator of how quickly power can be applied; top speed, the indicator of how efficiently and massively power can be produced and used. These measures increase at each iteration of hypercar, but the increments are getting numerically smaller, and infinitesimally harder to perceive.

The fastest of the holy trinity, the Porsche 918 set a 0-60 time of 2.4s back in 2014. According to Autocar, the fastest production car acceleration in 2021 is delivered by two cars, the Ultimate Evolution Coupe and Dodge Challenger SRT Demon at 2.3s, neither of them hypercars, but manufactured back in 2015 and 2017 respectively. With 8 years of development, Porsche haven’t pushed performance upwards, but the cost of delivering performance downwards – the £84k Porsche Taycan Turbo matching the 2.4s delivered by the £2.5m Bugatti Chiron.

Acceleration is limited by a specific function of physics – namely friction. There’s a point of no return as to how much torque you can put through the wheels before the connection between tyres and tarmac ceases to function, no matter how much you pay for your car.

Top speed is governed by a different set of constraints. Top speed is essentially a war of attrition: car power versus air resistance. Hypercars have evolved in their ability to produce power and limit the resistance they offer as they pierce through the air.

In 2019 a modified Bugatti Chiron, driven by Andy Wallace (the same Andy Wallace who delivered that McLaren F1 record), hit a top speed of 304.77mph. At which point Bugatti politely bowed out of chasing top speeds in a mic-drop moment saying that they’ve proved a point. Smart move, as chasing these incremental gains is getting impossibly hard and, to be frank, irrelevant. That record was recorded under very precisely controlled conditions on Volkswagen’s Ehra-Lessien test track with a driver of uniquely exceptional talents. All of this avoids the fact that every country in the world has speed limits – even Germany has only a limited amount of its famously derestricted tarmac.

There is, of course, a safe environment to enjoy your multimillion-pound investment: the race track. As well as pushing the track credentials of your road-legal car there has been a glut of Track Day specials. These are track versions of the road car, being uninhibited by legislation that restricts the full suit of engineering prowess being thrown at the car. For those who were unlucky enough to miss out on the road going version, have a little more disposable income or even want to show off their Track Day special on the latest Cars and Coffee event, you can even get it converted back to road legal (Lanzante).

The Bugatti top speed figure was achieved under strictly controlled circumstances, on a stretch of road that only VW group are allowed to use, so a fair comparison will probably never exist. Under-standardised conditions, the record is now held by SSC. After some very dubious initial claims of 311mph (the internet geeks exploded on that one) a fully ratified figure of 282mph was logged.

So, if acceleration has reached its limit, top speed becoming unrealistically difficult to achieve, and frankly unusable, the remaining headline figure is horsepower. Efficiencies have eked out ever more from the chemistry of petrol but the internal combustion engine will always have a limit and there’s the inevitable trade off between weight and physical size. Up until recently a figure of 220PS/litre seemed to be about the limit. Along comes Koenigsegg Jesko (who are beginning to make a real name for themselves as true innovators) with an incredible 317PS/litre – step changes may still be possible.

So the humble petrol engine may not be at its limit just yet. In 2030, the automotive landscape will change forever. For years, the automotive industry has been easy pickings for the environmentalists, highlighting how our cities are becoming choked, the era of ‘big oil’ will come to an end. An ever increasing number of cities and national governments are joining the movement to ban new vehicles being produced or used unless they have zero tailpipe emissions. For car fans of a particular era, this is going to be a dilemma. By definition, ‘petrolheads’ like petrol. If the core hypercar market is enthusiast petrolheads, then we have a problem.

New technologies spur innovation so enter stage left: electric vehicles (EVs). From the incremental gains of optimised combustion flow, all of a sudden a gigantic leap was possible. 2000PS suddenly appeared easily deliverable. Newcomers like Rimac and Aspark joined traditional producers like Lotus and Pininfarina in seizing the opportunity. It seems that 2000PS is a magic figure that customers can cling to and EV technology of the 2020s can achieve. But at what cost?

Standing start acceleration times are still limited by tyres and top speed by aerodynamics, but where EVs stand alone is their ability to provide maximum torque at any time – gone are the inefficiencies of being at the wrong revs at any particular time. If the purpose of hypercars is to deliver race car credentials in a road legal package, then enhanced lap times must be the way to go. Cars need to carry their power source with them at all times whether that be a fuel tank or a battery. Batteries have the ability to deliver a lot of energy slowly producing range or a lot of power quickly producing speed. With the desire to optimise power to weight ratio, the weight of the batteries means that one lap of Nurburgring is possible, but that’s all. A one lap race may have limited audience appeal.

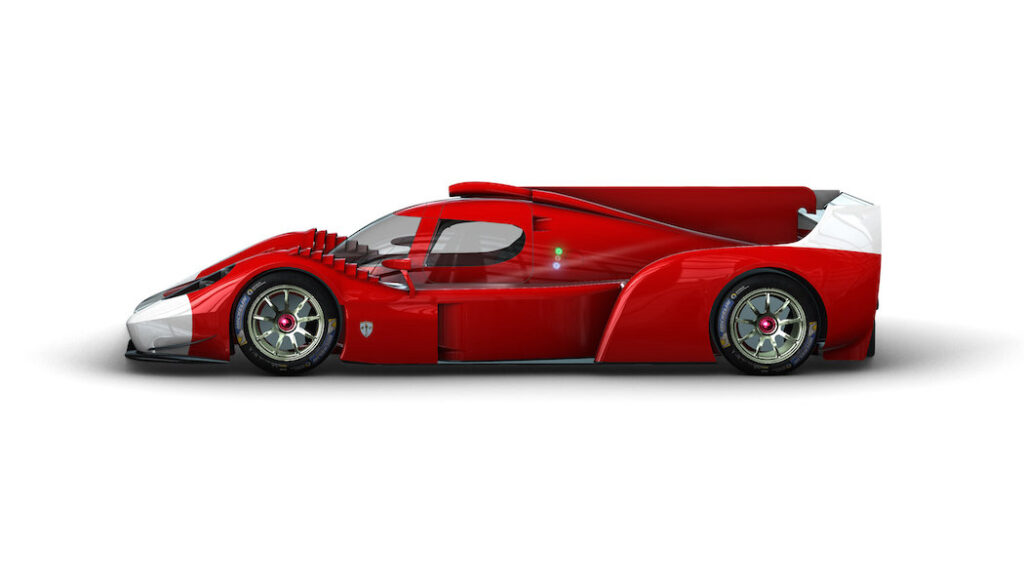

New regulations by the FIA and Le Mans organisers, the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, have created a new hypercar series starting in 2021 in an attempt to make the race more interesting and relevant, recreating a link between cars seen on the track and those you can buy – assuming you are a favoured multimillionaire.

There’s a rush on to beat legislation and get the ‘last of a dying breed’, the ‘last naturally aspirated’, the ‘last non-hybrid’, the ‘last internal combustion engine’. The world will then look towards zero tailpipe emissions – alongside this, the noise, smell and feelings will change. The rumble of explosions, the growl of exhaust gases escaping, the smell of volatile fluids evaporating – all gone – replaced by the whirr of electrons, the instant, mindbending torque.

Part of the definition of hypercars is about their limited availability. There is an economic model surrounding ‘Giffen products’ whereby the value is directly proportional to the rarity. Where hypercars have value in their engineering prowess and physical beauty we have seen that cheaper cars can have similar, if not better, performance metrics. Production runs of less than 500, less than 100 preferably, are the expected norm.

Car producers around the world have recognised the benefit of hypercars to their brand value and balance sheets. Many businesses have been lured by the thought of creating 200mil revenue by just finding 100 customers with margins in excess of 30%. Throw into the mix a bunch of frustrated engineers, designers and race car drivers and you can see the appeal. The appeal has been bought into by many, from differing backgrounds. As a non-exhaustive example, Lamborghini, Ferrari, Porsche, McLaren (traditional sports car manufacturers proving their prowess); Pagani, Glickenhaus, Gumpert (Geneva Motor Show staples in the business of making beautiful, extreme, or extreme beauty); Lotus, Aston Martin, Jaguar (heritage brands wanting to expand their worth); Brabham, Gordon Murray, AMG (race car credentials on the road); Czinger, Rimac, Aspark, Navran (disruptive tech innovators)

Corporate growth and customer demand are interesting bedfellows. Unlike mainstream vehicles, hypercars come with a predefined volume to help support the value. The 500 La Ferraris were snapped up, with demand reported as far exceeding supply. Without upsetting the original customers Ferrari saw an opportunity: La Ferrari Aperta – 200 additional units created by chopping the roof off and slightly increasing the power, yours for an additional £1m.

Ironically, bearing in mind the overdemand of La Ferrari, the roofless version was only available if you had bought the original. The logic, therefore, seems to be that within this customer base, one hypercar isn’t enough and to be honoured with a Ferrari product you need to have shown exceptional previous commitment to the brand.

Recent volte-faces from Aston Martin (Valhalla) and McLaren (Elva) have seen initial bullish volume predictions reduced for ‘the sake of customer value’ i.e. we don’t want to (or can’t) achieve the original volume. This suggests two possible issues, an insufficient product content or, more worryingly, an insufficient customer base.

Do we need another hypercar? If ‘we’ is defined as the buying public, then it seems we have got to a point where market economics are shifting the supply and demand curve. Although there is an increasing number of ultra-high-net-worth individuals (UHNWI) in the world, it appears that the number of car loving UHNWIs is growing at a slower rate than the number of available hypercars.

An alarming trend for making extreme, even more extreme has recently come to the fore. Base car too tame? Take the roof off. Wind in your hair, open top driving not exhilarating enough? How about wind in your face? The same, but with no windscreens. Aston, Lamborghini, McLaren and Ferrari all seem to think this is a good idea: if hypercars are limited in numbers, we can create limited editions of limited editions. Bugatti is renowned for creating 1 of 1 specials, although personalisation amongst these vehicles create one of a kind versions for everyone.

All of which adds to the total number of vehicles available to those willing UHNWIs.

In an attempt to reinforce uniqueness and emotional appeal, there seems to be a sudden patriotic rush with there being a raft of ‘first hypercar from …’ announcements. Whilst the national pride is commendable, it is hard to see in the global economy we inhabit that the first Polish hypercar (Arrinera) has any benefit over the first Lebanese hypercar (Lykan).

Surely enough is enough?

The posters adorning bedrooms around the world highlight the aesthetic appreciation of hypercars. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and whilst some designs are divisive there is no doubt that hypercars are 3D sculptures. No matter how good the photographer is they need to be seen in real life. The relative proportions, curves, forms, the way they catch the light where one piece morphs into the next. Whilst you could suggest that the world doesn’t need another unusable, fossil-burning, piece of machinery, I challenge anyone to suggest we have enough art in the world and that all the artists should immediately put their pencils down.

Dave Brailsford at Team Sky made popular the law of marginal gains, whereby a percentage point improvement by itself is not important, but if you add up many small efficiencies they become worthwhile and necessary. The level of detail provided within hypercar design is mind-boggling. Taking weight out becomes obsessive. New materials, new processes, new computing power. Airflow meticulously modelled using state-of-the-art systems gaining every possible efficiency.

An oft-used comparison is with watches. Quartz technology allowed a previously unheard of precision within a consumer product and delivered this at a price point akin to a posh coffee. However, materials, artistry, precision engineering and visible mechanisms still push prices of analogue watches into small house territory, despite being inferior at actually keeping time. The difference between a Maruti Suzuki and a Pagani Zonda Barchetta highlights that we are not just talking about a means of getting from A to B.

To some, hypercars are excessive, unnecessary and wasteful. Playthings for the rich, either in terms of business ventures or toys for grown ups. They are unable to be used anywhere near their full capability and, in fact, many are not used at all, stored to be looked at and, hopefully deliver a future pay day.

Hypercars are seen as a balance sheet prop with manufacturers fighting for a small number of customers. Just look at the amount of deposits that are locked up in someone else’s business – in a short-supply situation, deposits only exist to help cash flow of the manufacturing company. Even these customers must reach the limit of their garage capacity and investment portfolio at some point.

The world didn’t need a hypercar back in 1992, but it wanted one. Products like this sit stratospherically high on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, but I can guarantee that more will come. They represent an incredible blend of competitive spirit, human ingenuity, artistry and a splash of ego.

With the glut of current offerings customers will need to think more about their investments – having a hypercar is no longer a guarantee of future profits, choosing the right hypercar becomes an informed decision. Which unique, standout feature appeals to you? F1 engine (AMG), Supercapacitors (Lamborghini), aerodynamic fan (Murray), 3D printing (Czinger) innovative engines (Koenigsegg), timeless beauty (Bugatti)…

For me, if the hypercar market is too crowded and common-place.

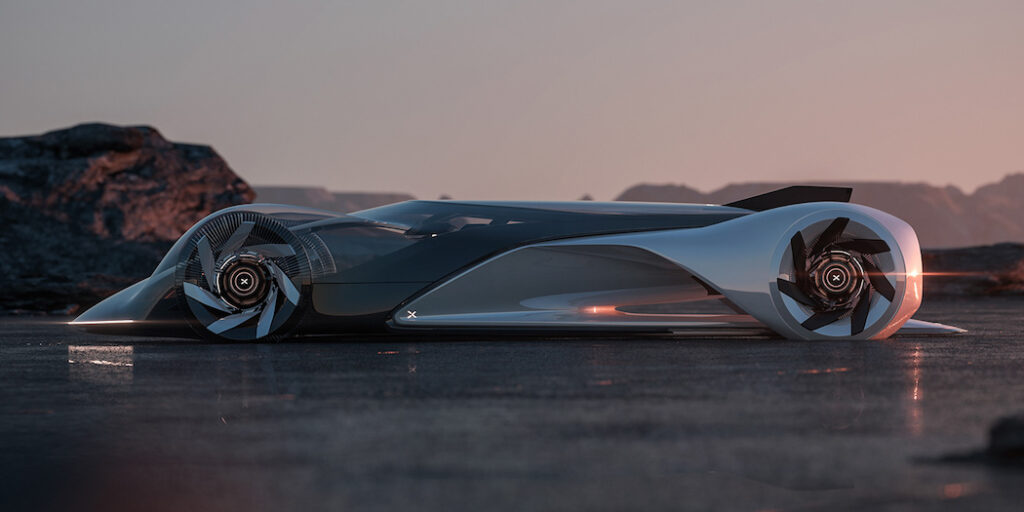

Bring on the megacar.