My partner is a bit older than me. Not enough for it to be a problem. We are both from the same decade and share lots of common history – but we’ve been together for a while and we’re getting to know each other pretty well.

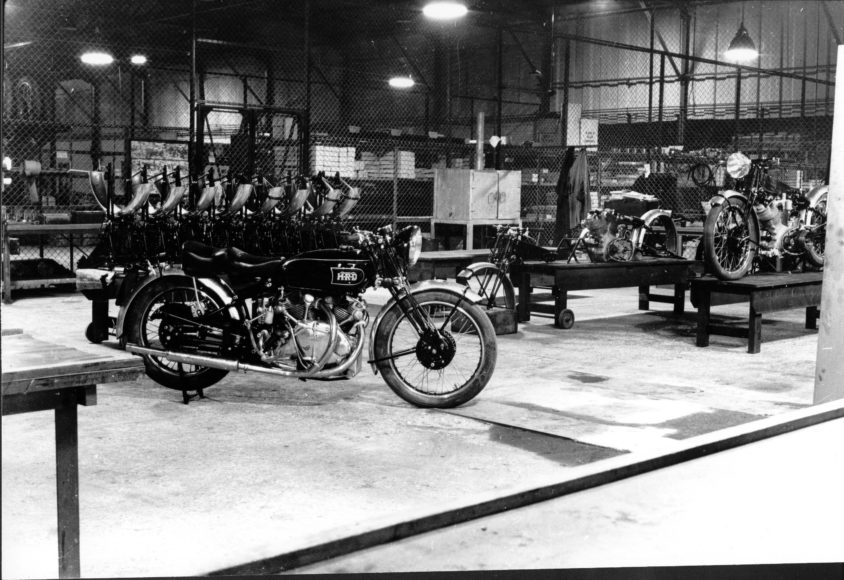

She is a 1952 “C” Series Vincent Rapide. In her day, she was racy as hell and just about the fastest thing on two (or four) wheels. She is still a decent performer, and she is absolutely beautiful – so beautiful that sometimes I go out into the garage just to stare at her.

Tell any grown-up motorcyclist that you ride a Vincent and there will be a short period of silence – time to think ‘what the hell is a Vincent?’ or ‘lucky git’, depending on life experience.

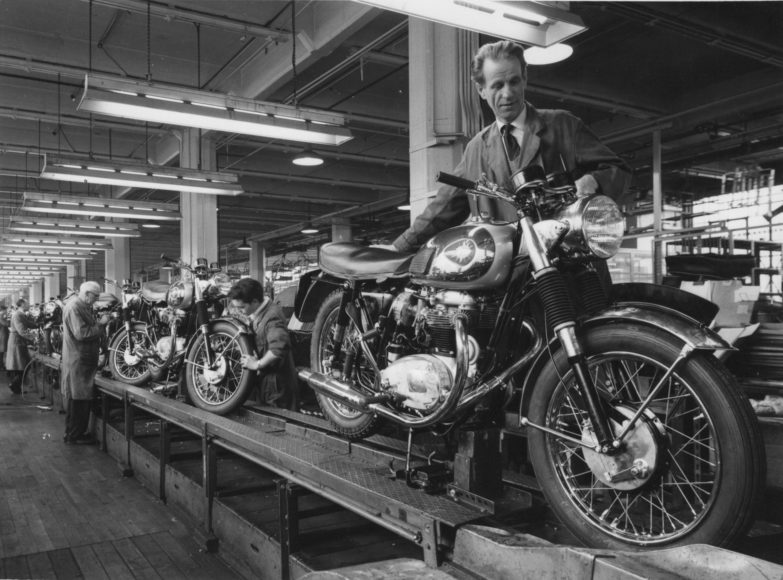

I wanted a Vincent very badly. Reaching biking maturity in the 1970s, my first bikes were British, cheap and pretty ropey. As was normal in those olden days, I went through the full gambit of ancient (even then), totally gutless 197cc Villiers, powered Fanny Bs and James’, and then moved up to 250cc BSAs and a half-decent Royal Enfield before taking my test, which allowed access to “proper” Triumphs and BSAs.

In the days when a “500” was considered a “big bike”, Vincent’s mighty 998cc twin was King of the Road – and would only feature in our wildest schoolboy fantasies.

Even then, Vincent’s were rare. There was a lad who strutted about town with “Vincent” painted artistically on the back of his leathers (I’m certain he never owned one) and that was about as close as I got. Gradually, my teenage dream of Vincent ownership (which lasted well into my thirties) was lost in contemplation of life’s (and wife’s) new goals.

But always, at the back of my mind, was a guilty residual Vincent lust. The occasional close encounter – almost entirely in museum collections – left me drooling. I knew that I would never be able to afford one – and I now know that I still can’t – but I succumbed to temptation bought one anyway.

There is the clever way to buy a Vincent: speak to specialist dealers and scan auction catalogues, join the owners’ club, speak to existing owners and beg advice, choose your model carefully, check provenance, history and engine numbers and, if you find a machine that you think might suit, get someone who really knows what they are doing to carefully inspect it for you.

Or you could do what I did.

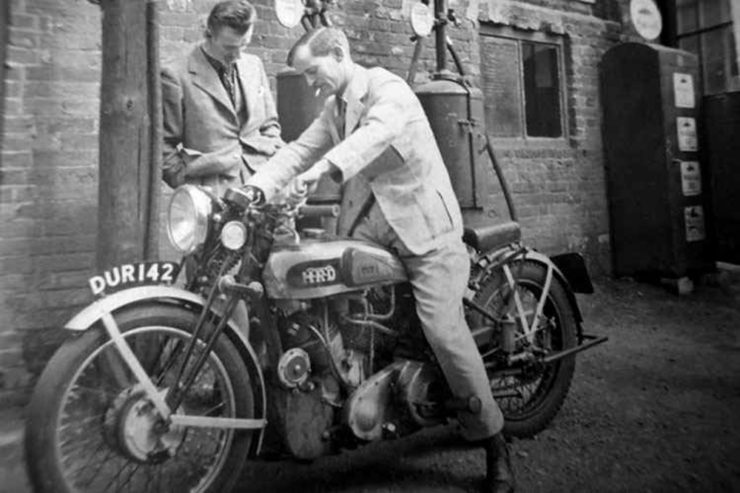

Paul’s 1952 “C” Series Vincent Rapide

Someone I had never met called me out of the blue and sent me a picture of a Vincent Twin that someone he knew had stored at the back of their garage. It had been his father’s bike and hadn’t seen the light of day for 18 years. I offered him a reassuringly large amount of money and the deal was done. And later, when I knew enough to be worried about what I had bought, I found I didn’t have to worry. I was very lucky. It wasn’t stolen. It wasn’t a bitsa bolted together from random parts, and it wasn’t seized, bent or buckled. It was a pucker, matching-numbers, one-previous-owner, 1952 Vincent Rapide.

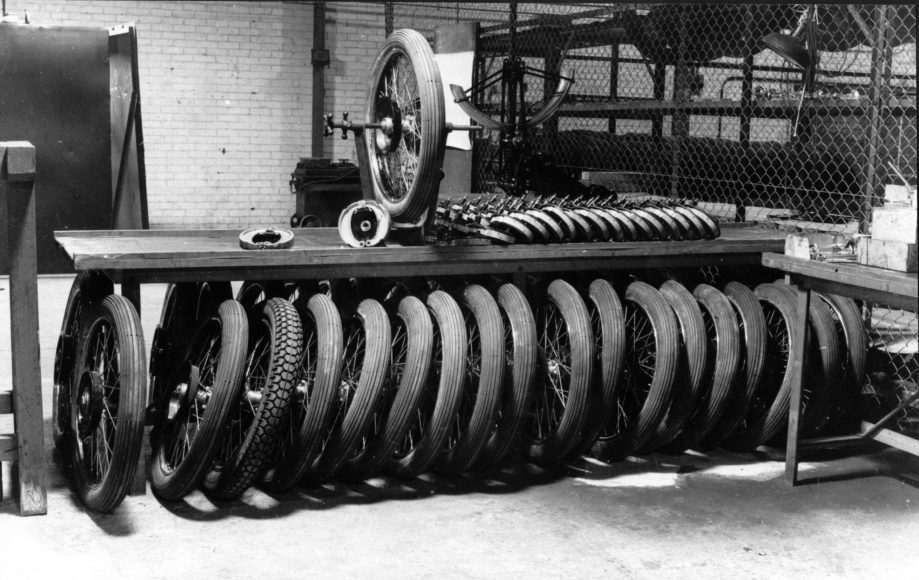

It was depressingly tired and looked very sad – and it didn’t work. Unless you really know what you are doing, you probably don’t rebuild a Vincent twin-engine yourself. Many years of motorbike mechanics have taught me how little I know, so I sent the bike off to one of the very few acknowledged experts for an engine strip and rebuild. They told me it would only take a year and, if they were careful, cost only as much as a new Triumph. Fortunately, the rebuild took just over two years, which gave me nearly enough time to save up the amount that it went overbudget by.

So, I got it home. Complete, rebuilt and running. Except for a few non-essential parts (such as carburettors, clutch and a seat) and with a fuel tank that had a marvellous period patina (and leaked pints of petrol all over my crotch).

Gradually, I’m starting to get it sorted. The tank has been to the strippers (paint strippers, not the other sort), to the man that brazes the cracks and silver-solders, the man who reseals it, so that It can take modern petrol, then to the man who paints it, and eventually to the man who does the gold-lining and transfers.

The Norton clutch that was a “racing” modification in the 60s has been rebuilt twice, had new plates and springs fitted and then the whole thing thrown in the bin because, although it never slipped, it never released properly either (it’s been replaced by a multi-plate clutch from the wonderful Vincent Owners Club Spares Company).

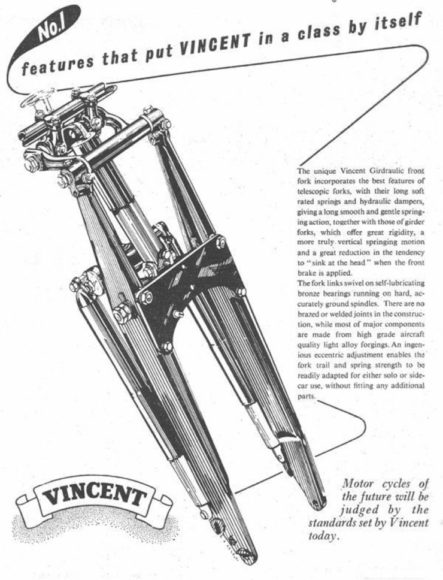

She’s not easy to live with. Boy, does she need constant fettling – constant care and attention, an oil change every 1,000 miles, checking, adjusting, and regular maintaining – to keep her at her very best. And of course, you’ll need a whole new set of tools – unless you own predominantly Whitworth spanners and have boxes of BSF-threaded nuts and bolts on your workshop shelf. She can be difficult to get going. Jump on, tickle the carbs, lift the decompressor lever and ease her over onto the “long rock” (i.e. just past compression on the rearmost cylinder) kick like billy-o and hope she doesn’t break your ankle. There’s no ignition key or steering lock – but you couldn’t steal it unless you knew what you were doing.

And for anyone who has mostly ridden bikes built in the last 40 years, she’ll keep “wrongfooting” you; her gear lever is on the right and configures one up, three down rather than the usual left-footed one down, five up. And that means that the brake pedal is on the left – which is fine until, in a moment of panic you stab down with your right foot and, instead of slowing down, you change up a gear.

But she’s really worth it – really, really worth it. Because riding a 1952 Vincent is the purest full-proof essence of wind in the hair, unfettered, rumbustious, forget where you should be and just go where you want to, motorbiking. It’s like catching the perfect wave, galloping into battle on a huge white stallion and racing around Brooklands in a vintage Bentley all on the same afternoon. It’s devil-may-care, hooligan motorcycling that is as respectable as afternoon tea at the vicarage. I love it.

Of course, I’ve been unfaithful. I’ve dallied with Ducatis, relied on BMWs, even enthused about a Suzuki (once, until I knew better). And my current, captivating mistress is a one of a long line of splendid Triumphs. But these are indeed mistresses – and that’s a completely different sort of relationship.

The most rewarding partnerships take the most work: patience, understanding, care and attention, time and sometimes expense. But then there is the return: the pride of ownership, the joyful appreciation of performance and the envy of one’s peers.

Richard Thompson wrote a song about a ’52 Vincent. As far as I know, it’s the only motorbike song written about a specific model. There is a line that goes “Nortons and Ariels and Beezers won’t do, they don’t have the soul of a Vincent ’52”. Very astute Richard. You summed it up beautifully