If you were to compile some of the most famous interviews of the 20th Century, no doubt John Lennon interviewed by Jann S Wenner, Marlon Brando by Truman Capote and Malcolm X by Alex Haley would all feature high in the list. But none have made an impact on the collective psyche as much as Sir David Frost’s interview with President Richard Nixon. In honour of the passing of Sir David Paradine Frost, OBE, we bring you one of Sir David’s last interviews – with Peter J Robinson in 2012.

Some two years ago, I decided that a new magazine that we were preparing to launch needed a big name, to give us the weight required to be taken seriously in the market.

On many a Sunday afternoon, when I was too young to protest, my dear grandmother would take me to church. Upon our return, my grandfather would sit me down and explain that I would ‘learn more in ten minutes watching Frost on Sunday than I would at church’. This resulted in a lifelong hunger for current affairs.

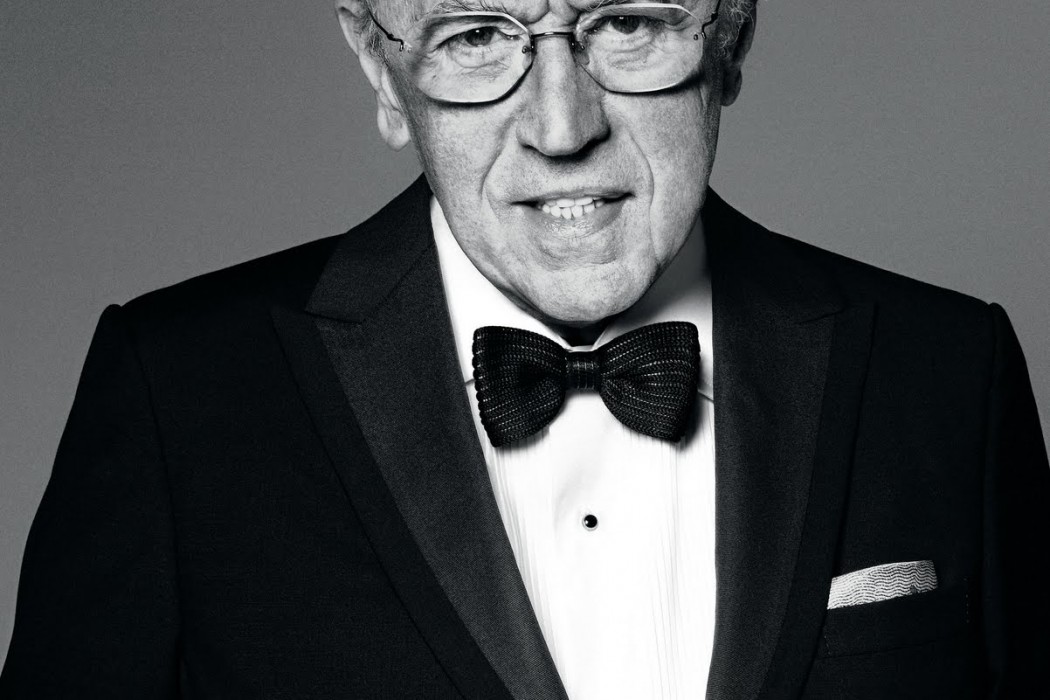

The 73-year-old son of a methodist minister, Sir David Frost became a household name on both sides of the Atlantic. After studying at Cambridge, he came to television in the early 1960s, presenting the groundbreaking BBC show ‘That Was The Week That Was’. In 1969, he also introduced the much-criticised trial by television, notably of Emil Savundra – head of a cut-price car insurance company that swindled thousands of motorists.

In 2011, I began the task of securing an interview with the monolith of broadcast journalism, Sir David Frost. Having interviewed six American presidents, eight prime ministers, several members of the Royal Family, and a galaxy of celebrities, I had little regard for my chances.

I initially sent Sir David’s assistant an overly-polite e-mail, asking if Sir David might have the time to consider an interview and feature for the front cover of the new title. To my amazement, she asked for details to be sent over, along with a copy of the title. At this stage, we didn’t have a title; all we had was the teaser issue, and a few well-designed pages and front cover put together for the media men. So, with bated breath I sent a copy to Sir David’s assistant, along with a hand-written letter thanking her for her help and explaining why a full issue of the magazine was not included.

After a few months of gentle nudging, I received news that Sir David wanted to discuss the interview with me. Saying I resembled a deer in the headlights would be unfair to the deer. A date was set (avoiding Sir David’s numerous commitments with Al Jazeera) for January 2012. I was asked to call Sir David, but despite two calls, he was unavailable at the times we had planned. Later that evening, whilst sat enjoying a drink in a local bar in Bristol, my phone rang. I answered it with my usual “Good evening, Robinson speaking”.

“Hello Peter, it’s David Frost, apologies for earlier. How are you?”

I almost dropped my drink, as I ran towards the doors of the bar to find a quiet area. “I’m well, Sir David, many thanks for calling. How are you?”

“I’m well,” came the reply.

Sir David had an almost Panglossian ability to stay positive in any situation. We discussed the interview, I explained our aims for the title and that, given my grandfather’s influence, I would be extremely pleased if we could interview him for the title. He accepted and asked that we set things up with his assistant after his return from Russia, post-interview with Vladimir Putin.

After a few more months of wrangling, the date was set for the 30 April 2012 at 3:00pm. When interviewing a man of Sir David Frost’s calibre, your research programme becomes a job in itself. I trawled through transcripts, watched the Nixon tapes for weeks and finally set myself a list of considered questions for the day. Given the timing and Sir David’s calendar, a telephone interview was the quickest route. Had we not had a print deadline, there is no doubt that we would have held off for a face-to-face interview. In some ways, the telephone interview yielded more material, as it was agreed that the telephone conversation would be recorded. I sat down in a separate office at 2:30pm and went over my questions. There was some safety from embarrassment, in that we were not face to face, but this would still be one of the most important interviews I would ever conduct.

____________________________________________________________

I was intrigued as to how Sir David managed to maintain such a disciplined approach and not, like so many interviewers, lose his cool with his subjects?

“I am very fortunate in the sense that I don’t normally get nervous, and even before the vital Watergate sessions of the Nixon interviews, I wasn’t nervous then either. I was concentrating, focusing, lasering in on the subject we were about to discuss and so on, but I don’t get nervous in that sense, which is obviously a great plus for interviewing, because often your first task is to relax the person your interviewing. If you’re nervous and un-relaxed yourself, that’s much more difficult.”

This leads me onto an area which I’m positive has been covered in excruciating depth. I feel like I should take some advice from Sir David and avoid the subject altogether, as let’s face it, what could be left to tell? I hazard a question: I can imagine that when interviewing President Nixon you made it clear from the outset that you were there to get answers?

“That’s right. Obviously some of the famous questions are adlibbed, but others are ones that you know you have to get an answer to. So, one concentrates on getting to those vital questions, but at the same time, in any interview, you’ve always got to be ready for a subject that you’re not expecting to come up that seems very fruitful. For instance, some great material came during mine and President Nixon’s ‘small-talk’ time. He had no small-talk, yet he insisted upon five minutes of it before each meeting. His verbal clumsiness was odd, because he was such a professional politician. Once he said, ‘Did you do any fornicating this weekend?’ He was trying to be one of the boys with me, but he got the words wrong. Lovers don’t call themselves fornicators any more than freedom fighters call themselves terrorists.”

Nixon may well be considered to be Sir David’s crowning achievement. It’s been said that he sacrificed a lot to get the interview – be it fiscally, commercially and through relationships. I ask whether, from the outset, he had the conviction that Nixon would open up on camera.

“Well, I was extremely hopeful that we would get him to open up on some of the key topics, but perhaps not all. In fact, what happened in the end is we went further – he went further – than we could have even predicted in terms of his confessions.”

Even today, Sir David seems every bit enthused as he was some 30 years ago. I pry, asking how it felt when Nixon did utter those infamous words.

“When the president does it, that means it’s not illegal,” he replies candidly. “He is cementing his ignominy there and then. Sometimes you’re delighted when someone is being very frank about a subject. Then your task, obviously, is to persuade them to go further and sometimes that is just by a short pause or a silence and the person comes forward with more things to say. So, if there is a silence, it’s a question of working out whether it’s potentially a very fruitful silence, or whether they have just forgotten what they were going to say.”

With such a varied history of interviewing high-profile people, one wonders who’s left to interrogate.

“I look forward very much to my next interview with Vladimir Putin, who is a fascinating man to interview. We’ve had two sessions, which were both very fruitful, one when he was acting president at the beginning of 2000, and the other before his state visit to the UK. Vladimir Putin is a very intriguing and provocative figure.”

It should make for an interesting interview given the increased scrutiny on the Russian government, in respect of freedom of speech. I’m keen to ask Sir David what he thinks will happen to investigative journalism, given the ongoing Leveson inquiry exploring the boundaries of journalism and notions of privacy.

“Obviously there are times when it appears that investigative journalism is under threat, and given the recent fuss over the bugging and all of that, it has looked as though investigative journalism could be. At the same time, a lot of the pressure has been towards more free speech rather than less. It could go in a way that makes investigative journalism more difficult, or it could make it more free, and I suppose the recent stories that have emanated from the Sunday Times about Peter Krellis show that investigative journalism is alive and well at the moment. It needs vigilance now because it’s very important that the outcome of all these enquiries is not to lessen the freedom of speech in this country, but to increase it. Lessening the freedom of speech would have dire consequences.”

I think it’s fair to say that Sir David has done his fare share for the cause. Choosing Al Jazeera was a bold choice in 2005. The station was mainly known in the western world for carrying exclusive Al-Qaeda messages. With many news outlets willing to bend over backward for Sir David’s services after leaving Breakfast with Frost, what gave this western unknown the edge?

“The reason that Al Jazeera was such an irresistible opportunity was that I felt that it might be the last time that a brand new news network covering the world would actually emerge. It made Al Jazeera English’s trailblazing plans very much irresistible. When Al Jazeera English started and when we started our show, Frost Over the World, they had 50 countries and 20 million households, in terms of reach. In the six years – it’s amazing that it’s six years – it’s risen to 130 countries and the reach has gone to 250 million households. So, the response to Al Jazeera has in fact been even better than one could have anticipated. It underlined that I felt I had made the right decision to say yes to their invitation.”

In 2011, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said that the network’s news coverage was more informative and less opinion-driven than American journalism. A great brand ambassador, if ever you needed the US administration’s support.

“Absolutely, that was a really strong endorsement, a very valuable one, and I’m sure that speech that she made did increase the positive impact of Al Jazeera English. The other thing they very wisely did was to say that we want to do a little more from the south of the world, rather than the north. We still cover the north of the world, America and Britain and so on, but we do tend sometimes in this part of the globe to underplay the rest of the world. It’s been a revelation to people – the material from South America and South East Asia and Africa. Africa has been a tremendously fruitful area for Al Jazeera English as well. It’s a very big part of the expansion.”

A credible news organisation opening up to a series of countries that are disenfranchised inevitably opens doors to individuals that the western press has never had the opportunity to gain access to, I would imagine?

“Yes, I think that Al Jazeera has developed as wide a possible an access and that has been a tremendous help. It really has helped to make it – not just because of the Middle East – the most genuinely, international network. That’s what’s underlined its impact I feel.”

We are certainly living in uncertain times – politically, economically and socially. Al Jazeera has been at the frontline for the last three years, covering a period of mounting unrest. Have you seen anything like this before and are you optimistic or pessimistic about the future?

“There was a real parallel back in the early 70s when the FTSE Index came down to something as low as 200 or 150. It was a real crisis and in a way it had even more impact that the current one, in terms of the sort of the crash that went around in 74. So that was very good training for this one, and in fact it probably had even more of an instant impact, although obviously there’s a continuing impact from this one.”

‘It seems that the only people weathering the financial impact these days are bankers and footballers’, I reply, deciding to change tact. There were stories that, growing up, you were interested in becoming a professional footballer for Nottingham Forest. Actually, I’m told you were rather good. Does your interest in sport extend to rugby?

“Yes, but not as passionately as football. Even though at my grammar school, Wellingborough Grammar School, they played rugby, I was playing for the local football team on a Saturday. I had to do my best when playing for my house during the week, but somehow manage to be selected for the first or second fifteen at the weekend. It was a pretty good juggling act.”

You always cite your interview with Sammy Davis Jr. as a great moment. My grandfather introduced me to the Rat Pack at a very young age, so I have to ask, was he every inch the entertainer he seemed?

“I’m so glad you raise the question of Sammy Davis Jr., because I think he was undoubtedly the greatest all-round entertainer the world has ever seen. He was so generous, because at the beginning of the 70s, I was doing ‘The David Frost Show’ in New York, and the rules of the talk show were that people got a minimal fee of $350 dollars. I think it’s only $500 odd now. So, $350 – and in addition to appearing for the interview, we had an orchestra, Sammy sang eight songs with the band, did about twenty impressions in the conversation, and did a wonderful dance. At the end of the show, he said ‘Thank you, David, I must thank you’. I said absolutely not, I’m the one that should be giving the thanks, because what you have given us here is just magic.

Sammy said ‘Whenever I want to give a friend of mine a present, I never like to just get them something from the shop, I like to give them something of my own’. At which point, he took off his magnificent diamond watch and gave it to me. It was a breathtaking moment, just incredible, and it became my most prized possession for about 12 years, until it was stolen from a hotel room. But it was just a typical example of what a generous soul Sammy Davis Jr. was, as well as a magnificent artist.”

Having interviewed such an eclectic mix of stars from the stage and screen, it’s no surprise that Sir David returned to the BBC this year, with a guide to the art of television interviewing, called Frost on Interviews.

How has the interview changed since you first started?

“Over the last 50 or 60 years, from the very bland interviews that people did with politicians back in the ‘50s, interviewing in politics has got sterner and tougher, which is all for the good. At the same time, in terms of film stars and celebrities, interviews have got softer, because more and more spin doctors are getting involved. Tony Blair made policy up on the air. In 2000, when he was under pressure over the NHS, he told me he was going to boost the level of spending on the NHS to the European average, which was not what he’d told Gordon Brown who, by all accounts, was furious. The next Thursday I went for drinks at Number Eleven and saw two treasury mandarins. One of them said, ‘You cost us £15bn on Sunday morning’. And the other one said, ‘No, it was much more than that’.”

You say interviews were previously bland, but did anyone stick out? Who influenced you back then?

“The interviewer who most influenced me was John Freeman. His interviews were called ‘Face to Face’ in the late 50s. They were stunning in the sense that they were so in-depth and to the point. He was also a very serious interviewer. But in terms of getting to the basics, which I think a lot of interviewing is about, answering the question ‘what makes people tick’, he was at the forefront of developing the questions on that front.”

Freeman’s manner was neither aggressive nor provocative, but the questions were fairly forthright, combining that with the camera work of the show which focused almost exclusively on the face of the interviewee, the interview was more like a session on a psychiatrist’s couch.

“It had an element of that certainly didn’t it,” Sir David replies. “That’s a very interesting observation.”

You have been noted for your friendly, non-aggressive approach to interviewing. How do you view the Paxman approach?

“[Laughs] Well, obviously I never like to comment on colleagues, but the basic point is that it’s no good going into an interview in a really combative way unless you’ve got the goods. I always remember one remark that the late Labour leader John Smith made to me after the last interview we did together. He said, ‘David, you have a way of asking beguiling questions with potentially lethal consequences’. I said I would be very happy to have that on my tombstone. In other words, yes, of course you can be confrontational, as long as it’s a real confrontation. Doing it in order to sound tough, but without the goods, it won’t work.”

“Well, we’ve done 28 minutes, but we’ve covered the field I hope?”

‘You’re timing it, Sir David?’

“No, I just have a clock in front of me.”

‘Well, I have it at 27 minutes and 34 seconds’.

He laughs, “Well, we’re in agreement on everything then.”

At this point, our time is up. Sir David charismatically wishes me good luck with the new title and offers to help with anything else I might need. His final act of kindness was to sign a copy of the title for me, an item that I promptly had framed and will cherish for years to come.

From myself and the whole team at The Review, requiescat in pace, Sir David.

Sir David Frost, OBE, 7 April 1939 – 31 August 2013.